Editors Note: Malcolm A. Goldstein is a contributing blogger for 1898 Revenues. This post is part of a continuing column on the companies that used proprietary battleships.

On April 30, 2011, a post on this site featured a check written to Gilbert Brothers of Baltimore. The check was special because 4 half cent gray documentary stamps were used to pay the 2 cent check tax. The post encouraged Malcom Goldstein to begin research on Gilbert Brothers:

It is a cold early February, 1903 day in Superior Court of the City of Baltimore, MD. The plaintiff, a Dr. (!!?) George Brehm of Rolandville, MD has alleged in his complaint that he went blind on July 27, 1898 two days after drinking three bottles of Jamaica ginger, a popular tonic, manufactured by the Baltimore drug wholesaler and manufacturer, Gilbert Brothers & Co. He states that he bought the bottles from a storekeeper on Elliot’s Island, Dorchester County, where he then lived. He seeks $30,000 damages.

Brehm’s is but one of five such claims, in aggregate seeking over $100,000 damages, pending against Gilbert Brothers & Co., owned by defendants, the brothers John J. and William E. Gilbert. A year earlier, another plaintiff, one Henry W. Jackson, of Keswick, Albemarle County, Virginia, had commenced trial in the same Superior Court of his $25,000 claim of blindness caused by drinking in 1899 the same Jamaica ginger manufactured by Gilbert Brothers & Co. Suddenly, at the opening of the third day of trial on Saturday, May 17, 1902 (a municipal service available on Saturday - how different the world really was!), Jackson withdrew his lawsuit and immediately filed a new one seeking $50,000, alleging an even broader basis for the wrongs committed by the Gilberts. In this trial, both Brehm’s attempt to introduce Jackson’s testimony from the earlier trial and his attempt to introduce his own expert chemist’s analysis of Gilbert’s Jamaica ginger done two years after Brehm’s blindness occurred have been thwarted by the trial judge. Yet that judge has not made the Gilberts’ victory a certainty, for he has also rejected the Gilberts’ motion to have him dismiss the case as a matter of law at the close of Brehm’s evidence (which would have had the effect of denying the jury the opportunity to make findings of fact). He has ruled against the Gilberts and in favor of Brehm that the facts alleged, if found true by the jury, might constitute a tort, or legal wrong, rather than accepting the Gilberts’ claim that Brehm’s facts, even if accepted as true, in no way constitute a legal wrong. (If the meaning of the prior sentence doesn’t immediately register, read it again, and it will gradually make sense. Such distinctions were, and remain, the essence of legal maneuvering, which ever warms the stony cold cockles of lawyers’ hearts.)

The so called “Wood Alcohol” cases have “excited great interest” throughout the drug, medical and ophthalmic worlds, which been watching and commenting in the trade journals on their progress for several years now. As the matter swiftly draws to a jury determination of liability, the facts have been fully marshaled. One journal reports a former employee has testified on Brehm’s behalf that the formula for the Gilberts’ Jamaica ginger during the period between 1897 and 1900 contained 30 percent wood alcohol, as well as 50 percent grain alcohol and 20 percent water. All articles agree that Brehm’s ophthalmologist and druggist have testified that wood alcohol - in pure form called “Columbian spirits” - is far more poisonous than grain alcohol, is never intended for human consumption and, in fact, is the only cause of plaintiff’s blindness.

And yet, another account indicates that the Gilberts have not only conceded Brehm’s percentage makeup of the mixture, but have also crowed that 65,376 bottles of that very product had been sold during the same period. The medical experts employed by the Gilberts have contradicted Brehm’s, arguing that “Columbian spirits” are no more poisonous than grain alcohol. One testified that he had consumed an ounce twice a day, as well as feeding a teaspoon to his cat every day for a month, and neither he nor the cat had suffered harm. Another testified that he had consumed one and one-half ounces within a span of three hours without any difficulty. To cinch the defense’s argument, William E. Gilbert himself takes the stand. He testifies both he and his family tried the formula before it was sold to the public and, moreover, that the concoction is intended to be a medicine not a beverage. To contradict his statement, Brehm then introduces into evidence, over the angry objection of the Gilberts, the Gilberts’ Jamaica ginger tonic bottle itself, whose label asserts that the preparation is a “delightful beverage in the hot summer months.”

Now the Gilberts make a final dramatic gesture to confirm their Jamaica ginger is not poisonous. With jurors and spectators watching, William coolly drinks an ounce of “Columbian spirits” and, again, repeats his performance one and one half hours later. All are aghast. Commentators report that while the Jamaica ginger “was freely diluted with water,” “no ill effects were experienced.” (The court journal officially records that two ounces of water were added to the “Columbian spirits” in each instance.) The evidence closes, and after the judge’s inevitable drone about the law it must apply to the facts it will determine, the jury retires to deliberate whether the Gilberts have blinded Brehm with their Jamaica ginger tonic made from wood alcohol.

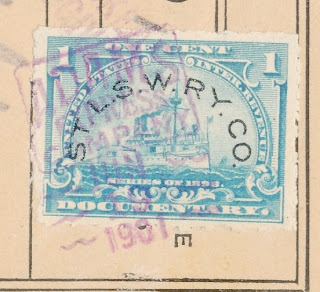

As they deliberate, let us examine the rest of the history of Gilbert Brothers & Co. The 1903 trial was probably the most striking event in the jumbled detritus of recorded coincidences and happenings from which we now attempt to reconstruct its history. Actually, a recent posting on this blog, spotlighting a check sent to Gilbert Brothers & Co in 1899, served to call this article into existence. As the cancels displayed (courtesy of Robert Mustacich) demonstrate, at the turn of the Twentieth Century, Gilbert Brothers & Co. was among a number of large and thriving drug businesses located in Baltimore. While the roots of several of today’s largest pharmaceutical companies, can be traced to its local competitors, such as Sharp & Dohme and Merck & Co. (both possible future subjects of this column), Gilbert Brothers & Co. and its owners left no comparable mark.

With respect to the Gilberts themselves, possibly because of such events as the “Wood Alcohol” trial, they were not profiled in the local “who’s who” compilations of Baltimore’s cherished and influential sons. Oddly enough, lists of awarded municipal contracts published in contemporaneous building trades journals, do indicate that William E. Gilbert was mayor of Laurel, Maryland around 1907. John J. Gilbert entirely lacks even that present definition, but his furniture collection - including illustrations and vivid descriptions of scrutoires (combination bookcase and foldout desk), looking glasses and a scalloped dressing table, all obviously selected at much expense with great discrimination - was prominently featured in a compendium called Colonial Furniture In America published by one Luke Vincent Lockwood in 1913. The scalloped dressing table again drew comment in “The Architectural Record” magazine, on the occasion of the Lockwood book’s being enlarged and updated in 1921. For the rest, all that can be said is that John J. Gilbert died in 1923 and left a considerable fortune, $25,000 of which went to William.

The remainder of the corporate history of Gilbert Brothers & Co. can be inferred from oblique references found in various records currently available. The earliest extant almanacs are dated 1870, which roughly indicates the time of the company’s establishment. In 1892, the minutes of the National Wholesale Druggists’ Association reveal that the company participated on the “Box and Cartage” Committee that recommended wholesale druggists break out and list separately an additional charge for packing and handling of goods instead of building the cost into the price of the drugs themselves. In 1889 or 1895, the company registered its trademark for what appears to have been its most popular product, Yager’s Cream Chloroform Liniment. In 1895, it trademarked a headache remedy called “Anti-Fag.” Alfred E. Mealy, another officer of Gilbert Brothers & Co., is listed as the holder of a patent, also issued in 1895, for the display box for “Anti-Fag.” Mealy, now as similarly anonymous as the Gilberts, later became president of the company, and also died in 1923, after forty years of faithful service.

Through the years, the references to Gilbert Brothers & Co. are scattershot. One trade journal mentions fire damage to the company’s plant in 1899, and another a 1904 suit by a retailer against Gilbert Brothers & Co. and other local wholesalers accusing them of price fixing (although the journal confidently predicted that the suit would never come to trial). In 1906, the U.S. government counted Gilbert Brothers & Co. large and important enough to name it as a defendant in its industry-wide price fixing suit against both the wholesale and retail druggists and their associations. This suit, settled without a trial by entry of a consent decree in 1907, certainly made illegal (and perhaps ended once and for all) the “drug cartel’s” many direct and indirect schemes to set and maintain retail drug and patent medicine prices by barring trade with wholesalers and retailers who wanted to sell these products at a discount. Another extant document reveals that on June 1, 1909, the Treasury Department issued one of its periodic circulars - with the strict admonition to its revenue collectors to place a copy in the hands of each druggist in their districts - ruling that Gilbert Brothers & Co.’s Rejuvenating Iron and Herb Juice was “insufficiently medicated” to permit its sale as a beverage without a special additional tax, even if sold as a medicine - one tonic among many on a very long list of such “alcoholic medicinal preparations” similarly treated in the Department’s bulletin. In other words, if a druggist wanted to sell that “Juice,” even as medicine, he had to have a liquor license above and beyond his druggist’s certificate.

Over the years, ads for products of Gilbert Brothers & Co. seem to have been most regularly published in the Southern Planter, a farming journal. The remedy most often featured was Yager’s Cream Chloroform Liniment, described as a “soothing external remedy for man or beast,” although in its many ads the company also recommended its Sarsaparilla with Celery for such conditions as eczema and baldness, and its Honey-Tolu for coughs. Standards must have gradually tightened over the years after the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act, but even in the early 1930s, the company - as many other wholesalers and manufacturers also did at the time - still forfeited to the Food and Drug Administration at least one shipment of patent medicines which was seized as misbranded after it shipped “in interstate commerce” from Maryland to New York. After that last record of official action against it, Gilbert Brothers & Co. seems to vanish from currently available sources.

However, even without Gilbert Brothers & Co., Yager’s Liniment (now sans “Cream Chloroform”) can still be obtained on-line, apparently now manufactured by one Oakhurst Company of Levittown, NY, which has gathered to itself a number of famous old patent medicines (or at least the rights to the use of their names). There are no ambiguities about the current incarnation of the liniment: camphor and turpentine oil are disclosed as the active ingredients. Such old-fashioned “external remedies” seem to have the greatest lasting power, since they don’t raise questions of internal poisoning such as the one presented in the “Wood Alcohol” cases.

And those jury deliberations, too, ultimately proved to be inconclusive. After fourteen days, the jury, confused and conflicted by the discrepancies between Brehm’s and the Gilberts’ expert witnesses, and, no doubt, impressed by William E. Gilbert’s sweeping gulp of a gesture, remained hung. The judge discharged it without its reaching a verdict. Shortly thereafter, a drug trade journal succinctly reported that all five cases were settled privately out of court. The amounts of the settlements, like so much else about Gilbert Brothers & Co., were not reported.

Two digressions, in the nature of footnotes, add current relevance to the story of Gilbert Brothers & Co. First, on the question of what quantity of wood alcohol makes it dangerous for human consumption, no less august and hoary an authority than Wikipedia itself today declares flatly that “[o]ne sip [of wood alcohol] (as little as 10 ml) can cause permanent blindness by destruction of the optic nerve and 30 ml is potentially fatal” (referencing a 2007 scientific article). Makes one wonder what William E. Gilbert was drinking that cold February day in 1903, and whether John J. was trying to repay him all those many years later with the $25,000 bequest! Second, the 1930s scandal caused by the plague of paralysis visited upon impoverished drinkers quaffing Jamaica ginger tonic tainted with a different chemical in their quest for a cheap whiskey substitute, is a major subplot of the book, and current movie, Water For Elephants by Sarah Gruen. History class for this period dismissed!