Friday, August 31, 2012

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Chicago Board of Trade Members: William Hood

WM. HOOD

SEP

24

1898

Langlois scan

William Hood was noted as a broker in the 1900 list of CBOT members. He was #4378.

I haven't found too much on Mr. William Hood. However, his daughter, Alice, married Nikola Trbojevich, a nephew of Nikola Tesla and also an inventor of note, including the hypoid gear. While the connection to the stamp above and the hypoid gear might be a stretch, I figured a little summary on this important invention would be edifying:

hypoid gear

Hypoid gears are found within the rear axle differential of some automobiles and trucks. The gears allow for the transfer of torque 90 degrees. From the Engineers Edge website: "Hypoid gears combine the rolling action and high tooth pressure of spiral bevels with the sliding action of worm gears."

Monday, August 27, 2012

Sunday, August 26, 2012

Saturday, August 25, 2012

On Beyond Holcombe: International (Stock) Food Company

Editor's Note: Malcolm Goldstein is a contributing blogger for 1898 Revenues. This post is part of a continuing column on the companies that used proprietary battleships.

The International Food Co, a manufacturer of animal feed whose name was changed to International Stock Food Co about 1902, is known in philatelic circles both for its elaborate cancels on several values of the battleship revenue issue and its intricate and multicolored envelopes, now prized as advertising covers. The fronts of these envelopes sported the company logo, essentially variations on a picture of a merry pig, watched by a smiling horse and a cow, about to dig into a box or bucket of the company’s three-in-one feed. The backs of the envelopes showed the manufacturing plant in Minneapolis, MN, sometimes pitched at an angle highlighting the spires (calling to mind the English Parliament buildings), and sometimes focused on the massive building itself towering over a busy street. The accompanying legend boasted that the plant was the largest of its kind in the world and contained eighteen acres of floor space, sustained by a company capitalized successively at $1,000,000, $2,000,000 or, even later, $5,000,000. An ad mailed in one of the company’s fancy envelopes around 1902 explained why the company chose to use revenue stamps on its products during the Spanish-American War, thus subjecting itself to the tax assessed on proprietary medicines:

However, the real color in the International Food Company was its dynamic sole proprietor, Marion Willis Savage. Born in 1859 in Ohio, he grew up in West Liberty, Iowa, the son of a country doctor. Savage began his career as a farmer, but was flooded out. He then took a position as a clerk in a local drug store. From observing the local farmers, he concluded that there was a fortune to be made by manufacturing a cheap, reliable livestock feed. After an early manufacturing venture with a so-called friend who absconded leaving him broke, he moved to Minneapolis and started over in 1886. Finding the right advertising pitch in thriftiness, he always stressed that his feed was really “3 feeds for 1 cent.” By 1895, utilizing the know-how of experts working at the state agricultural school, Savage had constructed a large enough business to support his purchase of the grand Exhibition Building in Minneapolis, which he thereafter pictured on his advertising, and had affiliated plants not only in Toronto and Memphis, but also in England, Ireland, Scotland, France, Germany and Russia. Because of his great showmanship and energetic promotion efforts, Savage was identified by his contemporaries as “the second P.T. Barnum.”

Savage had now amassed enough of a personal fortune to begin building his dream estate. He chose a location eighteen miles south and west of Minneapolis on the Minnesota River at a town called Hamilton, renamed Savage in 1904 in his honor. Here he began to nurture his true love which was horse racing and horse breeding. On one side of the river, he built an enormous and elaborate horse farm, known locally as the Taj Mahal, consisting of a barn with an octagonal rotunda 90 feet high and 100 feet long, from which protruded huge wings of stalls housing a capacity of 130 horses, together with a mile race track and a half mile race track, which was entirely enclosed and lit by 1400 windows. On the bluff on the other side of the river, he built his country house situated so that he could stand on his front porch and time the horses as they went around the track.

The horses with which Savage populated the farm assured that the crowds would come, for he purchased, as its centerpiece, Dan Patch. In an age when proper jockeys still rode in sulkies behind the horses, Dan Patch, at age 4, stood 16 hands tall (5'4'’) and weighed 1,165 pounds. He was a pacer (as opposed to a trotter which had a different style of gait) who had never lost a race and had already garnered over $13,000 in winnings for his prior owners. In fact, by 1902, no other owner would even race horses against him. Yet, Savage paid the princely sum of $60,000 for Dan Patch in 1902, and later bragged that the price was the cheapest he ever paid for one of his champions, since Dan Patch is thought to have earned well over $250,000 for Savage in many, many different ways. For example, the farm itself became a tourist attraction, accessible by a river boat plying the river, or, after 1907, on Savage’s railroad, the Minneapolis, St. Paul, Rochester and Dubuque Electric Traction Company. That railroad quickly took on another name, the Dan Patch line.

Through canny and lavish promotion, including Dan Patch’s own private railroad car painted white and decorated on either side with his framed portrait, Savage built Dan Patch into the preeminent pacer and harness racing champion of the first decade of the Twentieth Century, as famous in his time as Sea Biscuit or Secretariat. One writer has since described Dan Patch as: “the epitome of excellence, the superlative of greatness and the zenith of equine superiority.” First and foremost, Savage used Dan Patch to endorse International Stock Food’s products, credited with saving the horse’s life during grave illness in 1904, but also lent his name to endorse everything from automobiles to tobacco. Crowds of 40,000 and 50,000 regularly attended his appearances at state fairs and exhibition horse races, done only against the clock. Savage even re-named the farm the International 1:55 Stock Food Farm in 1906 after the racing association would not accept Dan Patch’s latest pacing mile time as the official world record (breaking his own record set the year before) because of a rule change .

Whole articles could be devoted to Dan Patch. In the Internet era, entire web pages are dedicated to him, following in the path of books previously written about him. In 1949 a fictionalized movie, The Great Dan Patch, ostensibly recounted his story. After suffering from lameness, Dan Patch retired from racing in 1909. Put out to stud, he did not prove to be a great sire and his heirs never shone as brightly as he did. Even as Savage fielded champion after champion attempting to supercede Dan Patch’s records in racing circles, he never lost his attachment to Dan Patch, who continued to live on Savage’s farm. Both fell ill on July 4, 1916. Dan Patch died of an enlarged heart on July 11. Savage, hospitalized for minor surgery, was deeply upset to hear of Dan Patch’s death, but quickly recovered enough to order Dan Patch stuffed. However, before his order could be executed, Savage himself suddenly died. Most attributed Savage’s death to a broken heart. Possibly giving credence to these stories, his widow, Marietta, quickly countermanded the order and had Dan Patch buried quietly and privately somewhere unknown to this day on the farm grounds. Savage’s son Harold took control of the International Stock Food Company, and it continued to exist into the 1930s. Fisher’s Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities lists the company as dissolved in 1935. Although the farmland has been in continuous cultivation since Savage’s death, the farm buildings fell into disrepair just after Savage’s death, and have all disappeared. The country house on the other side of the river passed to the Minnesota Masonic Home, which used the building as its headquarters for a number of years, but ultimately demolished the structure in 1950. Nothing remains of either Savage’s original farm or country home. Only the memory of Dan Patch lingers.

The International Food Co, a manufacturer of animal feed whose name was changed to International Stock Food Co about 1902, is known in philatelic circles both for its elaborate cancels on several values of the battleship revenue issue and its intricate and multicolored envelopes, now prized as advertising covers. The fronts of these envelopes sported the company logo, essentially variations on a picture of a merry pig, watched by a smiling horse and a cow, about to dig into a box or bucket of the company’s three-in-one feed. The backs of the envelopes showed the manufacturing plant in Minneapolis, MN, sometimes pitched at an angle highlighting the spires (calling to mind the English Parliament buildings), and sometimes focused on the massive building itself towering over a busy street. The accompanying legend boasted that the plant was the largest of its kind in the world and contained eighteen acres of floor space, sustained by a company capitalized successively at $1,000,000, $2,000,000 or, even later, $5,000,000. An ad mailed in one of the company’s fancy envelopes around 1902 explained why the company chose to use revenue stamps on its products during the Spanish-American War, thus subjecting itself to the tax assessed on proprietary medicines:

"At the time of our last war nearly every ‘Stock Food manufacturer’ made a sworn statement to the government that they did not use any medicinal ingredients in their ‘Stock Foods’ and did not claim any medicinal results. The government then allowed them to sell their ‘Stock Foods’ without paying the war tax and on the same basis as ‘common foods’ like corn and oats. A preparation of this kind that does not contain medicinal ingredients is of no more value to you than common ‘mill feeds’... These people either fooled the government or are trying to fool you by asking a ‘medicinal price’ for something that does not contain medicinal ingredients. Are such business methods honest? .... We paid $40,000 War Tax because ‘International Stock Food’ was a High-Class Medicinal preparation...”

Chappell/Joyce International Food Co. Type 1 cancel, 1898; Type 2s follow with full dates:

1899

1900

1901

However, the real color in the International Food Company was its dynamic sole proprietor, Marion Willis Savage. Born in 1859 in Ohio, he grew up in West Liberty, Iowa, the son of a country doctor. Savage began his career as a farmer, but was flooded out. He then took a position as a clerk in a local drug store. From observing the local farmers, he concluded that there was a fortune to be made by manufacturing a cheap, reliable livestock feed. After an early manufacturing venture with a so-called friend who absconded leaving him broke, he moved to Minneapolis and started over in 1886. Finding the right advertising pitch in thriftiness, he always stressed that his feed was really “3 feeds for 1 cent.” By 1895, utilizing the know-how of experts working at the state agricultural school, Savage had constructed a large enough business to support his purchase of the grand Exhibition Building in Minneapolis, which he thereafter pictured on his advertising, and had affiliated plants not only in Toronto and Memphis, but also in England, Ireland, Scotland, France, Germany and Russia. Because of his great showmanship and energetic promotion efforts, Savage was identified by his contemporaries as “the second P.T. Barnum.”

Savage had now amassed enough of a personal fortune to begin building his dream estate. He chose a location eighteen miles south and west of Minneapolis on the Minnesota River at a town called Hamilton, renamed Savage in 1904 in his honor. Here he began to nurture his true love which was horse racing and horse breeding. On one side of the river, he built an enormous and elaborate horse farm, known locally as the Taj Mahal, consisting of a barn with an octagonal rotunda 90 feet high and 100 feet long, from which protruded huge wings of stalls housing a capacity of 130 horses, together with a mile race track and a half mile race track, which was entirely enclosed and lit by 1400 windows. On the bluff on the other side of the river, he built his country house situated so that he could stand on his front porch and time the horses as they went around the track.

The horses with which Savage populated the farm assured that the crowds would come, for he purchased, as its centerpiece, Dan Patch. In an age when proper jockeys still rode in sulkies behind the horses, Dan Patch, at age 4, stood 16 hands tall (5'4'’) and weighed 1,165 pounds. He was a pacer (as opposed to a trotter which had a different style of gait) who had never lost a race and had already garnered over $13,000 in winnings for his prior owners. In fact, by 1902, no other owner would even race horses against him. Yet, Savage paid the princely sum of $60,000 for Dan Patch in 1902, and later bragged that the price was the cheapest he ever paid for one of his champions, since Dan Patch is thought to have earned well over $250,000 for Savage in many, many different ways. For example, the farm itself became a tourist attraction, accessible by a river boat plying the river, or, after 1907, on Savage’s railroad, the Minneapolis, St. Paul, Rochester and Dubuque Electric Traction Company. That railroad quickly took on another name, the Dan Patch line.

Through canny and lavish promotion, including Dan Patch’s own private railroad car painted white and decorated on either side with his framed portrait, Savage built Dan Patch into the preeminent pacer and harness racing champion of the first decade of the Twentieth Century, as famous in his time as Sea Biscuit or Secretariat. One writer has since described Dan Patch as: “the epitome of excellence, the superlative of greatness and the zenith of equine superiority.” First and foremost, Savage used Dan Patch to endorse International Stock Food’s products, credited with saving the horse’s life during grave illness in 1904, but also lent his name to endorse everything from automobiles to tobacco. Crowds of 40,000 and 50,000 regularly attended his appearances at state fairs and exhibition horse races, done only against the clock. Savage even re-named the farm the International 1:55 Stock Food Farm in 1906 after the racing association would not accept Dan Patch’s latest pacing mile time as the official world record (breaking his own record set the year before) because of a rule change .

Whole articles could be devoted to Dan Patch. In the Internet era, entire web pages are dedicated to him, following in the path of books previously written about him. In 1949 a fictionalized movie, The Great Dan Patch, ostensibly recounted his story. After suffering from lameness, Dan Patch retired from racing in 1909. Put out to stud, he did not prove to be a great sire and his heirs never shone as brightly as he did. Even as Savage fielded champion after champion attempting to supercede Dan Patch’s records in racing circles, he never lost his attachment to Dan Patch, who continued to live on Savage’s farm. Both fell ill on July 4, 1916. Dan Patch died of an enlarged heart on July 11. Savage, hospitalized for minor surgery, was deeply upset to hear of Dan Patch’s death, but quickly recovered enough to order Dan Patch stuffed. However, before his order could be executed, Savage himself suddenly died. Most attributed Savage’s death to a broken heart. Possibly giving credence to these stories, his widow, Marietta, quickly countermanded the order and had Dan Patch buried quietly and privately somewhere unknown to this day on the farm grounds. Savage’s son Harold took control of the International Stock Food Company, and it continued to exist into the 1930s. Fisher’s Manual of Valuable and Worthless Securities lists the company as dissolved in 1935. Although the farmland has been in continuous cultivation since Savage’s death, the farm buildings fell into disrepair just after Savage’s death, and have all disappeared. The country house on the other side of the river passed to the Minnesota Masonic Home, which used the building as its headquarters for a number of years, but ultimately demolished the structure in 1950. Nothing remains of either Savage’s original farm or country home. Only the memory of Dan Patch lingers.

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Cotton "Factors": Heard Brothers

Cotton Exchange, New Orleans, 1873, by Edgar Degas

Cotton Factors, or businessmen that bought and sold cotton and acted as middlemen for cotton growers, were a mainstay of the southern cotton economy. Some of the gentlemen in the Degas painting above were no doubt cotton factors.

RN X7 imprinted check drawn on the account of Heard Brothers

Bob Hohertz scan

The Heard Brothers, cotton factors, bought and sold cotton and manufactured and sold fertilizer, but as Harold Woodman writes, the cotton factor did more than just act a middleman for cotton:

From King Cotton and His Retainers: Financing and Marketing of the Cotton Crop of the South by Harold D. Woodman:

"Although the factor served as the planter's banker, factorage houses were not banks in the real meaning of the word; that is, unlike commercial banks, factors did not have the power to create money either through note issue or deposit loans. They did, as has been shown, often open a line of credit to a customer, allowing him to draw on them as funds were required. In doing so, however, they merely loaned money on hand (their own funds or those being held for a planter) or they borrowed from other sources. In the former case they could be compared to modern savings and loan associations or credit unions; in the latter case, they acted much as do present day finance companies. The factor, then, was the planter's banker only in a very general sense: he handled his funds, arranged his credit, and paid his bills.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Chicago Board of Trade Members: Richardson & Company

Richardson & Co.

document fragment from a futures contract

Langlois scan

Richardson & Company, grain merchants, had 5 members of the CBOT with the name Richardson in 1900:

#3977 Dan E. Richardson

#6467 Erskine Richardson

#3657 R. Julius Richardson

#6724 Roderick D. Richardson

#5775 Roderick W. Richardson

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

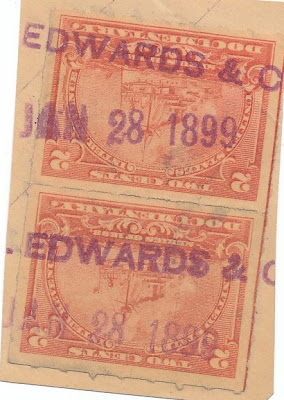

Chicago Board of Trade Members: James A. Edwards

J. A. EDWARDS & CO.

JAN 28 1899

Langlois scan

James A. Edwards was member #2175 of the CBOT.

From The History of The Board of Trade of the City of Chicago, 1917:

member of the organization. His labors not only constituted a potent factor in the progress and development of the city, but were an inspiring influence, and even though he has passed from the scene of earthly activities his work remains as a force for good in the community. He not only achieved notable success in business, but in his home, in social and public life, he was kind and courteous, and no citizen of Chicago was more respected or enjoyed the confidence of the people or more richly deserved the regard in which he was held.

Mr. Edwards was born in Baltimore, Maryland, November 11, 1854, a son of Dr. Edward W. and Catherine R. Edwards, who were pioneers of Chicago, having removed to this city from Baltimore when our subject was six years of age. The father was a physician and surgeon, and was one of the learned men of his profession who gave impetus to the work of science in this city. After acquiring a substantial education in the public and private schools of Chicago, James A. Edwards began his business career when sixteen years of age with the old established Board of Trade firm of Culver & Co. He remained with that house until the close of the year 1872, and in the following year entered the employ of Dennis & Ingham, who were in the same line, and continued with the latter firm until 1874. In May, 1875, he embarked in business for himself, becoming an exponent of the grain commission trade, of which he became one of the prominent and influential representatives. To meet the demands of the constantly expanding trade, and as a matter of commercial expediency, the business was incorporated in 1898, and was also reorganized in 1912, although Mr. Edwards remained the executive head until his retirement from business activities in April, 1916.

He was a loyal and most valued member of the Board of Trade during his entire identification with the organization, and was one of those upright and sagacious men who have aided in furthering the prosperity and prestige of this great institution. He joined the Board May 21, 1877, and was one of its active members until April 19, 1916, when he transferred his membership to his son Donald Edwards. Coming to this city when a small boy and entering business life when a lad of sixteen, Mr. Edwards grew up with Chicago during the period of its most marvelous development, and through pluck, perseverance and honorable dealing he became one of its substantial and most valued citizens. A man of unusual public spirit, interested in local affairs and proud of the city in which much of his activities and mature manhood were passed, he was a powerful factor in the furtherance of any measure which had for its aim the advancement of the people or the betterment of existing conditions. To sketch in detail his work during his active business life would be a task of no small moment, however agreeable and interesting. It must suffice to say in conclusion that his labors were of the most earnest character, that they were exceedingly comprehensive, and that they contributed in a most important degree to the development of the agricultural and commercial prosperity and wealth of the section in which they were performed, and in no slight measure to the material advantage of the whole country. Although making no claim to greater credit than that which belonged to one, who by wise and persistent effort, advanced his own fortune and at the same time that of hundreds, even thousands, who shared in one way or another in his enterprises, a discriminating pubHc sentiment will not fail to accord him a front rank among the commercial benefactors of the country.

On April 12, 1882, Mr. Edwards was united in marriage with Miss Minnie E. Paine, a daughter of the late Joseph E. Pame, of Brooklyn, New York, and a woman of exceptional mental capacity and much beauty of character. They became the parents of two sons and two daughters ; the sons, Kenneth P. and Donald Edwards, are both active members of the Board of Trade and are classed with the enterprising and conservative commission merchants of the city. The former joined the Board December 23, 1908, and the

latter became a member by transfer of his father's membership on April 19, 1916, and both are associated with the firm of J. A. Edwards & Co. The daughters are Marjorie Edwards, who resides with her mother, and Dorothy, who became the wife of Frederick A. Rogers, of Indianapolis, Indiana.

The family home has been in Hyde Park for many years. It is a hospitable one, where good cheer abounds, and where the family's numerous friends are ever welcome. Although unostentatious in manner, Mr. Edwards was recognized as a man of earnest purpose and progressive principles. He always stood for the things that were right, and for the advancement of citizenship, and was interested in all that pertains to

modern improvements along material, intellectual and moral lines. Though he had many warm friends and was prominent in social circles, he was devoted to the pleasures of home life, and his happiest moments were always spent at his own fireside. He found pleasure in promoting the welfare of his wife and children, and was a kind husband and an indulgent father.

He was identified with various social organizations of representative order, including the Chicago Athletic Association, the Forty Club and the Midlothian and South Shore Country Clubs. In the Masonic fraternity he had completed the circle of both the York and Scottish Rites, besides having been affiliated with the adjunct organization, Medina Temple of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. His ancient craft affiliation was with Ashland Lodge, No. 308, Free & Accepted Masons.

Although he was a stalwart Republican in his political affiliations he took no part in politics aside from casting the weight of his influence in support of men and measure, working for the public good, and at no time was animated with a desire for public office. In business life he was alert, sagacious and reliable; as a citizen he was honorable, prompt and true to every engagement, and his death, which occurred January 15, 1917,

removed from Chicago one of its most valued citizens.

Monday, August 20, 2012

New York Stock Brokers: Simon Borg & Company

1901 Poors Manual Advertisement

S B & Co

die cut initials

Langlois scan

In 1896, Wall Street was almost unanimous in its support for Republican candidate for President William McKinley and his "honest money" platform. In the November 4, 1896 edition of The New York Times, Leo Speyer was quoted:

Advices from abroad are all one tenor--encouraging. If we win the honest money victory we count upon we will find a quick and unhesitating response from investors on the other side of the sea. They will come in not as speculators merely, but as buyers, disposed to hold on a long time. Their influence in our security markets will be felt at once and be long lasting.

Clearly, Mr. Speyer and among others wanted to provide an indication that European capital just might stay away if the electorate went for William Jennings Bryan in the election.

Sunday, August 19, 2012

Chicago Board of Trade Members: William E. Webbe

W. E. Webbe & Co.

SEP 3 1898

CHICAGO.

David Thompson scan

William E. Webbe was a commission trader on the CBOT with member #2301

From the book Origin, Growth & Usefulness of the Chicago Board of Trade:

W. E. Webbe & Co., Commission Merchants, Room 52, No. 161 La Salle Street.--Among the leading and successful houses engaged in the grain and provision commission trade is that of Mssrs. W. E. Webbe & Co., whose offices are at No. 161 La Salle Street. Mr. W. E. Webbe has been a member of the Board of Trade since 1877, and is one of the most popular gentlemen connected with that body. He is also a member of the Chicago Produce Exchange, and possesses every facility for transacting human business under the most favorable auspices.

Mr. Webbe was born in England thirty one years ago. He has been in Chicago for the past eight years, and during that time won name and place among our most influential merchants. His career is one of which he may well feel proud, reflecting credit as it does both upon himself, the city of his adoption, and the various commercial organizations with which he has become so permanently identified.

Saturday, August 18, 2012

On Beyond Holcombe: Fairchild Brothers & Foster

Editor's Note: Malcolm Goldstein is a contributing blogger for 1898 Revenues. This post is part of a continuing column on the companies that used proprietary battleships.

Fairchild Brothers and Foster was another of a group of specialty drug manufacturing and supply companies that flourished in New York City around the turn of the Twentieth Century. It took its name in 1881, when the Fairchild Brothers, Benjamin and Samuel, brought Malcomb Foster into their partnership. The Fairchild brothers were born in Stratford, CT, Benjamin in 1850 and Samuel in 1852. They both studied at the famed Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, and trained as pharmacists at the older New York City pharmacy firm, Caswell, Hazard & Co. Samuel, the younger brother, also served a stint as a pharmacist with McKesson & Robbins. (These two long-lived and well-known companies also applied cancels to battleship revenues and will appear again in due course in this extended study).

In 1878, the two brothers launched their own partnership as Fairchild Bros. Foster, born in 1860 and another alumnus of McKesson & Robbins, although quite young, apparently made a significant contribution of capital to the firm when he joined it. The firm concentrated early in products to aid digestion, specializing in the production of the digestive enzyme, pepsin, and the entire peptonizing process. In the pre-analytic chemistry era of medicine, such pepsin fortified products were then considered by established medical authority to be particularly helpful to infants in developing proper digestive systems, to ill people in maintaining proper digestion against the ravages of disease and to old people in keeping their digestive systems strong into their dotage. Similar claims - probably based upon the same kind of “correct-hunch” (i.e. sounds right) but ultimately dubious science - are advanced today for iron-fortified or omega 3-fortified products. In support of its peptinized products, F B & F published several editions of its pamphlet “Handbook of Digestive Ferments.”

The company was often praised within the trade as a well organized and supervised, and it too escaped the scrutiny of the genuine quack medicine chasing reformers. For that reason, rather than concentrating on the specifics of its business, it might be more instructive to examine the sumptuous style of life a fairly small but specialized business like F B & F produced for its principals. In 1908, the Pharmaceutical Era, an industry publication, portrayed and described the offices of F B & F in the following manner:

Because of their wealth, the Fairchilds traveled in fashionable circles and mixed with others who had attained the rarified sphere of high society. In a 1914 compendium of lives of prominent Americans, Samuel Fairchild’s achievements and connections were listed as follows:

Samuel passed away at the age of 75 in 1927, and his older brother, Benjamin at the venerable age of 88 in 1939. Forbes, the youngest member of partnership died a year before Benjamin at age 78. The company itself, as often the case, did not survive the last of its founders for very long. It continued as an independent company only until 1946, when it was acquired by Sterling Drug Company, itself the survivor from among an amalgam of companies also launched in this period. By that time, the most well-known of F B & F’s products was Phisoderm, an acne fighting product still available today, although ownership of the product has changed a number of times since 1946, and the make-up of the product itself was altered in the 1970s after the Federal Drug Administration banned products which contained more than 1% hexachloraphene, then its principal active chemical agent.

Fairchild Brothers and Foster was another of a group of specialty drug manufacturing and supply companies that flourished in New York City around the turn of the Twentieth Century. It took its name in 1881, when the Fairchild Brothers, Benjamin and Samuel, brought Malcomb Foster into their partnership. The Fairchild brothers were born in Stratford, CT, Benjamin in 1850 and Samuel in 1852. They both studied at the famed Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, and trained as pharmacists at the older New York City pharmacy firm, Caswell, Hazard & Co. Samuel, the younger brother, also served a stint as a pharmacist with McKesson & Robbins. (These two long-lived and well-known companies also applied cancels to battleship revenues and will appear again in due course in this extended study).

Benjamin Fairchild, Samuel Fairchild, and Macomb Foster

In 1878, the two brothers launched their own partnership as Fairchild Bros. Foster, born in 1860 and another alumnus of McKesson & Robbins, although quite young, apparently made a significant contribution of capital to the firm when he joined it. The firm concentrated early in products to aid digestion, specializing in the production of the digestive enzyme, pepsin, and the entire peptonizing process. In the pre-analytic chemistry era of medicine, such pepsin fortified products were then considered by established medical authority to be particularly helpful to infants in developing proper digestive systems, to ill people in maintaining proper digestion against the ravages of disease and to old people in keeping their digestive systems strong into their dotage. Similar claims - probably based upon the same kind of “correct-hunch” (i.e. sounds right) but ultimately dubious science - are advanced today for iron-fortified or omega 3-fortified products. In support of its peptinized products, F B & F published several editions of its pamphlet “Handbook of Digestive Ferments.”

The company was often praised within the trade as a well organized and supervised, and it too escaped the scrutiny of the genuine quack medicine chasing reformers. For that reason, rather than concentrating on the specifics of its business, it might be more instructive to examine the sumptuous style of life a fairly small but specialized business like F B & F produced for its principals. In 1908, the Pharmaceutical Era, an industry publication, portrayed and described the offices of F B & F in the following manner:

Because of their wealth, the Fairchilds traveled in fashionable circles and mixed with others who had attained the rarified sphere of high society. In a 1914 compendium of lives of prominent Americans, Samuel Fairchild’s achievements and connections were listed as follows:

Samuel passed away at the age of 75 in 1927, and his older brother, Benjamin at the venerable age of 88 in 1939. Forbes, the youngest member of partnership died a year before Benjamin at age 78. The company itself, as often the case, did not survive the last of its founders for very long. It continued as an independent company only until 1946, when it was acquired by Sterling Drug Company, itself the survivor from among an amalgam of companies also launched in this period. By that time, the most well-known of F B & F’s products was Phisoderm, an acne fighting product still available today, although ownership of the product has changed a number of times since 1946, and the make-up of the product itself was altered in the 1970s after the Federal Drug Administration banned products which contained more than 1% hexachloraphene, then its principal active chemical agent.

Thursday, August 16, 2012

Cotton Buyers: Smith & Coughlan

RNX7 imprinted sight draft charged to Clifton Manufacturing in Clifton, South Carolina for 100 bales of cotton for $4809.26

Bob Hohertz scan

Bob Hohertz heeded my call last week for cotton-related material and sent in this scan of a draft from Smith & Coughlan, cotton buyers. A little history on this firm is found below. Smith & Coughlan had shipped by rail 100 bales of cotton to Clifton Manufacturing in South Carolina, and charged Clifton Mfg $4809 through this draft.

From the

HISTORICAL AND STATISTICAL REVIEW; MAILING AND SHIPPING GUIDE

(Illustrated) Birmingham, Anniston, Gadsden, Huntsville, Decatur, Tuscaloosa and Bessemer

THEIR MANUFACTURING AND MERCANTILE INDUSTRIES, HISTORY, PROGRESS, AND DEVELOPMENT

NEW YORK AND BIRMINGHAM

Southern Commercial Publishing Company.

1888.

SMITH & COUGHLAN, Birmingham and Gadsden. — No class of commercial business advances a city more than those who advance the farming interests of the country, and thereby the producing supply. This is done more particularly by the commission men of the city. The firm heading this sketch bas been in operation about five years, and have a ripe experience in the handling as well as in the markets for selling the fleecy staple.

With ample cash to buy, Messrs. Smith & Coughlan are prepared to make liberal advances on cotton. They have another office at Gadsden, Alabama, in connection with the cotton business. Mr. F. G. Smith is a native of Nashville, Tennessee. He has been engaged in the steamboat business for many years. He is well known in the city as President of the South Anniston Land Company. His partner, Mr. J. H. Coughlan, is a native of Boston.

Their long experience in the business, with their extensive correspondence and acquaintance with the cotton markets of the world, has fitted them to realize good prices for cotton, which brings them the most liberal orders. The firm is a leading one in the cotton trade, and is entitled to the confidence of the readers of the history of Birmingham, who have orders of cotton to give, and desire a good firm, possessed of executive ability in this line of business.

This is but a brief account of a firm which, in every way, is worthy of the success it has attained, and the esteem in which it is held by the entire communitv.

CLIFTON MANUFACTURING:

From the Textile History website:

Clifton Manufacturing Company was incorporated January 19, 1880 with a capital stock of $200,000 (1). Mills at this time were normally built along rivers where a change in slope gave opportunity to harness water power. With prior experience downstream on the Pacolet River, Edgar Converse, a native of Swanton, Vermont, organized cotton mill at Hurricane Shoals. The noted engineering firm of Lockwood Greene was selected to design the mill. Clifton Mill No. 1 (named or the cliffs overlooking the Pacolet), began manufacturing in 1881 with 7,000 spindles, 144 looms and 600 operatives, who lived in the nearby mill village. (2)

The company prospered and authorized another mill in August 1887. The new mill, named Clifton No. 2 was located just downriver on Cannon’s Shoals. Construction began in 1888 and began production in 1889 with 21,512 spindles, a three-fold increase over No. 1. Early products for these mills included sheeting, drills, and print cloth.

In May 1895, management authorized a third mill to be located just north of mill No. 1. This mill, Clifton No. 3, would have 34,944 spindles and 1092 looms. Albert H. Twichell succeeded Edgar Converse as president of Clifton Manufacturing upon the death of Mr. Converse in May, 1899. Clifton No. 3 opened in 1900.

he Flood of 1903: A devastating flood on June 6, 1903 tore through the valley and caused havoc. One witness said of Clifton No. 3, “The five-story, 50,000-spindle mill trembled for a while, then gave way, a wall of water rose 40 feet in minutes. Mill No. 1 was next in line. The entire mill village within 100 feet of the river was destroyed. One-third of the mill disappeared. When the water reached No. 2, it took away half the four-story mill.” (3)

Sources:

1. Teter, Betsy Wakefield, editor. 2002. Textile Town Spartanburg County, South Carolina, Hub City

Writers Project, Spartanburg ISBN 1-891885-28-6 Appendix.

2. Mike Hembree, The Birth of Clifton – Boom Town on the Pacolet

3. William M. Branham, The Flood of 1903 –Terror Along the Pacolet River p 77

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Chicago Board of Trade Members: McReynolds & Company

McReynolds & Company

NOV 1

Langlois scans

McReynolds & Company.

AUG 17 1899

document fragments from futures contracts

George S. McReynolds, CBOT Member #2502, ran this firm, and ran it into prison. Mr. McReynolds committed business fraud and was sentenced to Joliet prison. He was released early due to a sick mother. The New York Times told this rather brief story on August 26, 1910:

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Chicago Board of Trade Members: Jackson Brothers & Company

J. BROS. & CO.

AUG 14 1899

document fragment from futures contract

Langlois scan

There were many Jackon members of the CBOT and Jackson Brothers & Company, including:

#2935 Howard B. Jackson

#2081 William S. Jackson

#4669 Darius C. Jackson

From the History of the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago, 1917

William S. Jackson. — For nearly forty years the late William S. Jackson was a vigorous, honored and influential member of the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago, and his was the distinction of having served as its president in 1903 and 1904, his able administration having fully justified the honor thus conferred upon him by his appreciative fellow members.

It was his to achieve substantial success as a representative of the grain commission business in the western metropolis, and that success was won by worthy and legitimate means, as his course in life was ever guided and governed by the highest principles of integrity and honor and he fully merited the confidence and esteem that were uniformly reposed in him.

He was the virtual founder of the large and important commission business that is still continued by his brother, Howard B., and his son, Arthur S., under the firm title of Jackson Brothers & Company, and it is most gratifying to record that as public-spirited citizens and alert and progressive business men these two are well upholding the prestige of the family name. Mr. Jackson continued his active identification with the Board of Trade from 1876 to the time of his death, and he was summoned to eternal rest on the 18th of November, 1914, a man of strength of purpose and of the finest civic and business ideals.

William S. Jackson was born at Adrian, the judicial center of Lenawee county, Michigan, on the 4th of December, 1841, and this date indicates beyond peradventure that his parents were numbered among the pioneers of that section of the Wolverine state. In his youth Mr. Jackson received excellent educational advantages as guaged by the standards of the locality and period, and his higher academic training was acquired in the University of Wisconsin, at Madison. His father served as a sheriff in Wisconsin, at the time of the Civil War, and incidentally he himself was enabled to gain youthful experience in the position of deputy sheriff under his honored sire.

In 1875 Mr. Jackson, as a young man of thirty-four years, came to Chicago, and in the following year he became a member of the Board of Trade, through the medium of which he was destined to gain marked precedence and success as an influential exponent of the commission business in grain. His broad views and well fortified opinions made him for many years one of the leaders in the governmental affairs and general functional activities of the Board of Trade, but to the public in general he became better known for his civic loyalty and public spirit and for his active association with railway construction.

In 1896 he was elected to represent the old Third ward of Chicago on the board of aldermen, and of this position he continued the vigorous, faithful and valued incumbent for a period of eight years. His unfaltering loyalty was manifested in his earnest support of measures tending to advance the general welfare of the city of its people, and he was specially zealous in the advocacy of the important policy of effecting the elevation of railroad tracks within the city and in making municipal provision for the establishing of small parks. His personal charities and benevolences were unceasing and invariably marked by unostentatious and kindly zeal, besides which he was for many years a director of the United Charities of Chicago.

His political allegiance was given to the Republican party and his religious faith was that of the Presbyterian church. Monday, August 13, 2012

Sunday, August 12, 2012

Saturday, August 11, 2012

On Beyond Holcombe: Andrew Jergens Company

Editor's Note: Malcolm A. Goldstein is a contributing blogger for 1898 Revenues. This post is part of a continuing column on the companies that used proprietary battleships.

Andrew Jergens Company was among a group of soap making companies that originated in Cincinnati, Ohio. Its long and storied history, which expands to include lotions, perfumes and other beauty care products began around 1882. Philatelically, Jergens reached its zenith not during the Spanish-American War, when it merely applied hand cancels to the battleship revenue issue, but rather during World War I when it printed its cancel on the subsequent black proprietary revenue issue of 1914 to 1916, RB32 to RB64. While not entirely accurate, the corporate history does verify the surge in revenue usage during World War I.

Andrew N. Jergens, Sr. was born in 1852 in Schleswig, a southern province of Denmark invaded and incorporated into Prussia in 1864. However, before Schleswig changed hands, Andrew had emigrated with his family to Indiana in 1859. At twenty, he moved to Cincinnati, and, as with all creation myths, the story of the founding of his company is told in slightly different ways in different accounts. It is said that he and a man named Charles H. Geilfus, variously described as a fellow common laborer, neighbor or older soap maker, joined, either to reorganize Geilfus’s existing business in 1880 (or with one W.L. Haworth), to form a new partnership in 1882, one (or both) of which then became known as the Jergens Soap Company. Jergens apparently supplied the $5,000 capital necessary to finally get the operation launched, so the company bore his name. Whatever the romance behind this tale, focusing on Jergens’ singular bravado in investing his entire life savings, according to the Cincinnati street directories (now available on line), Geilfus was a soap maker in 1880, and the Western Soap Company (not the Jergens Soap Company) came into being in 1882.

In 1886, the Andrews Soap Co is listed in place of the Western Soap Co. According to the company’s website, by 1894, Jergens had brought his brothers, Al and Herman, into the company and it became known as the Andrew Jergens Company. The city directories do acknowledge the name change as of 1895. Geilfus, whatever his role in the company formation, was born in 1856 and lived until 1914. Geilfus, during his long tenure as a corporate officer, and Haworth, if at all, for an infinitely shorter microsecond, apparently subordinated their personalities to Jergens, and have left virtually no independent record of their existence behind them. The soap making company located its plant, with its one soap making boiler and twenty-five employees, in the slaughterhouse and meat-packing district of town to be able to obtain most of their needed raw materials easily from meat production waste. The one extra ingredient Jergens and his partners chose to add to usual soap mixture was coconut oil. The Andrews Soap Co sold coconut oil soap.

In 1901 the company, now definitely the Andrew Jergens Company, incorporated, with Andrew, brother Herman and Geilfus as its corporate officers. These three men inhabited lavish homes on three corners of the same intersection in the Northside neighborhood of Cincinnati known locally as “Millionaires’ Corner.” Jergens Park, a city park, now occupies the site of Jergens’ house, and one of its rooms, imported from Syria is preserved in the Cincinnati Art Museum as the “Damascus Room.”

The official company history indicates from 1898 to 1901, during the period when Jergens used the battleship revenue stamps, it continued to market coconut soap as its principal product. In 1901, this history continues, it evolved, in a single bound, from a soap company into a cosmetics company when it purchased the product lines and trademarks of the John H. Woodbury Company, makers, among other things, of Woodbury facial soaps, and the Robert Eastman Company, a perfume and lotion manufacturer. These purchases ignited the explosive growth of Jergens in the first decade of the 1900s from 25 employees to 1000 employees (and, indirectly, stimulated its need to use a printed cancel, rather than a hand stamp, on the black World War I revenue issue).

The contemporary record blurs the drama of the company’s single moment of transition. In the February 10, 1897 issue of a weekly drug trade publication, one short paragraph announced that the company had purchased the factory of the Eastman Perfume Company of Philadelphia and had taken control of the manufacture and sale of the Woodbury facial soap and cream, while leaving Dr. John Woodbury still in control of his Dermatological Institute located in New York. Beyond that news, the same concise blurb remarked that Andrew Jergens was on an extended trip to Mexico, and would attend to the necessary arrangements to effectuate these changes upon his return. The magazine speculated that the principal change would be an expansion of the company’s sales force. Thus, although the Woodbury purchase was finalized in 1901, the transition had already begun in 1897 under licensing agreements. While this account is less vivid than the company history - and is probably historically insignificant - this small correction of the historical record is attested mutely by the absence of battleship revenue cancels for either the Eastman or Woodbury companies.

No matter what the actual succession of events, the new products did change the nature of the Jergens company’s business. The hand cream formula bought from Eastman was marketed originally as “Jergens Benzoin and Almond Lotion Compound,” and later simply as “Jergens Lotion.” It proved to be an instant success and rocketed Jergens to the top of the newly emerging field of skin care products. Expanding upon the model of the varied line of Woodbury soaps, by 1911, Jergens was marketing 82 brands of fragranced soaps, mostly under the Jergens name. But the Woodbury soaps were proving as troublesome as they were profitable. Around 1906, Dr. John Woodbury claimed that Jergens had breached the 1901 purchase agreement by not following the prescribed medicinal formula for his Woodbury soaps, marketing cheap tallow soap as “Woodbury Soap” instead. Woodbury marketed his original formula under his own name as a “Woodbury’s New Skin Soap.” Jergens was forced to sue Woodbury for an injunction to bar him from marketing soap under his own name, since Jergens owned the rights to the Woodbury name under the 1901 agreement. By then, Jergens had brought the J. Walter Thompson agency in to create a new advertising campaign to market the Woodbury soaps, leading ultimately to the wildly popular slogan “A Skin You Love To Touch” (modified in the 1920s to “The Skin You Love To Touch”). While it is difficult to measure why this campaign produced such an iconic slogan and remained effective as a branding tool for so long, some observers have suggested the slogan’s success was rooted in its being the first subtle injection of sex into advertising. After litigation in a variety of courts as intricate and protracted as Dickens’ Jarndyce v. Jarndyce, in 1921, Woodbury’s cousin, William, ultimately extricated, by means of a tiny sliver of trademark rights held back in the original 1901 contract of sale, the right to produce a line of products under his own name, but not John’s. Further litigation between the company and William Woodbury circumscribed even that right in 1927, and as late as 1938, the various Woodbury interests were still suing each other over who owned what residual rights to the Woodbury name under the 1901 contract.

Andrew Jergens, always portrayed as hard working and frugal, remained at the head of his company until his death in January, 1929. His son Andrew N. Jr., born in 1881, succeeded him as president. Junior apparently was not terribly close to his driven father, but, nevertheless, as a dutiful son, started at the bottom of the company and worked his way up. When radio developed as an advertising medium in the 1920s, Senior endorsed the medium by diverting a portion of his advertising budget into radio advertising. Under Junior, the company sponsored Bing Crosby and Bob Hope in the 1930s, Walter Winchell, the most-listened-to and influential radio political columnist of his day, from 1932 to 1948, and Louella Parsons, his counterpart as a Hollywood gossip columnist between 1944 and 1954.

The company also innovated in the areas of using movie star endorsements and pioneered in marketing cosmetics in chain stores rather than beauty specialty shops. Along with strong advertising, the company produced new and more daring products, such as roll on deodorants and bubble bath, so that it was solid and established in the beauty care field when Junior died in 1967. American Brands, Inc. purchased the company in 1970, and a Japanese company, the Kao Corporation, purchased it from American Brands in 1988. As a wholly owned subsidiary of Kao, Andrew Jergens Company purchased the John Frieda Professional Hair Care Products business in 2002. While the company name was officially changed from Andrew Jergens to Kao Brands in 2004, the Andrew Jergens Company is still listed on the web as having a street address and telephone number in Cincinnati and new Jergens products are readily available on the web.

Jergens lotion in 2012

ANDREW JERGENS & CO.

1900

2c documentary battleship

Andrew Jergens & Company first appeared on this site in August, 2009.

Andrew Jergens Company was among a group of soap making companies that originated in Cincinnati, Ohio. Its long and storied history, which expands to include lotions, perfumes and other beauty care products began around 1882. Philatelically, Jergens reached its zenith not during the Spanish-American War, when it merely applied hand cancels to the battleship revenue issue, but rather during World War I when it printed its cancel on the subsequent black proprietary revenue issue of 1914 to 1916, RB32 to RB64. While not entirely accurate, the corporate history does verify the surge in revenue usage during World War I.

Andrew N. Jergens, Sr. was born in 1852 in Schleswig, a southern province of Denmark invaded and incorporated into Prussia in 1864. However, before Schleswig changed hands, Andrew had emigrated with his family to Indiana in 1859. At twenty, he moved to Cincinnati, and, as with all creation myths, the story of the founding of his company is told in slightly different ways in different accounts. It is said that he and a man named Charles H. Geilfus, variously described as a fellow common laborer, neighbor or older soap maker, joined, either to reorganize Geilfus’s existing business in 1880 (or with one W.L. Haworth), to form a new partnership in 1882, one (or both) of which then became known as the Jergens Soap Company. Jergens apparently supplied the $5,000 capital necessary to finally get the operation launched, so the company bore his name. Whatever the romance behind this tale, focusing on Jergens’ singular bravado in investing his entire life savings, according to the Cincinnati street directories (now available on line), Geilfus was a soap maker in 1880, and the Western Soap Company (not the Jergens Soap Company) came into being in 1882.

In 1886, the Andrews Soap Co is listed in place of the Western Soap Co. According to the company’s website, by 1894, Jergens had brought his brothers, Al and Herman, into the company and it became known as the Andrew Jergens Company. The city directories do acknowledge the name change as of 1895. Geilfus, whatever his role in the company formation, was born in 1856 and lived until 1914. Geilfus, during his long tenure as a corporate officer, and Haworth, if at all, for an infinitely shorter microsecond, apparently subordinated their personalities to Jergens, and have left virtually no independent record of their existence behind them. The soap making company located its plant, with its one soap making boiler and twenty-five employees, in the slaughterhouse and meat-packing district of town to be able to obtain most of their needed raw materials easily from meat production waste. The one extra ingredient Jergens and his partners chose to add to usual soap mixture was coconut oil. The Andrews Soap Co sold coconut oil soap.

In 1901 the company, now definitely the Andrew Jergens Company, incorporated, with Andrew, brother Herman and Geilfus as its corporate officers. These three men inhabited lavish homes on three corners of the same intersection in the Northside neighborhood of Cincinnati known locally as “Millionaires’ Corner.” Jergens Park, a city park, now occupies the site of Jergens’ house, and one of its rooms, imported from Syria is preserved in the Cincinnati Art Museum as the “Damascus Room.”

The official company history indicates from 1898 to 1901, during the period when Jergens used the battleship revenue stamps, it continued to market coconut soap as its principal product. In 1901, this history continues, it evolved, in a single bound, from a soap company into a cosmetics company when it purchased the product lines and trademarks of the John H. Woodbury Company, makers, among other things, of Woodbury facial soaps, and the Robert Eastman Company, a perfume and lotion manufacturer. These purchases ignited the explosive growth of Jergens in the first decade of the 1900s from 25 employees to 1000 employees (and, indirectly, stimulated its need to use a printed cancel, rather than a hand stamp, on the black World War I revenue issue).

The contemporary record blurs the drama of the company’s single moment of transition. In the February 10, 1897 issue of a weekly drug trade publication, one short paragraph announced that the company had purchased the factory of the Eastman Perfume Company of Philadelphia and had taken control of the manufacture and sale of the Woodbury facial soap and cream, while leaving Dr. John Woodbury still in control of his Dermatological Institute located in New York. Beyond that news, the same concise blurb remarked that Andrew Jergens was on an extended trip to Mexico, and would attend to the necessary arrangements to effectuate these changes upon his return. The magazine speculated that the principal change would be an expansion of the company’s sales force. Thus, although the Woodbury purchase was finalized in 1901, the transition had already begun in 1897 under licensing agreements. While this account is less vivid than the company history - and is probably historically insignificant - this small correction of the historical record is attested mutely by the absence of battleship revenue cancels for either the Eastman or Woodbury companies.

No matter what the actual succession of events, the new products did change the nature of the Jergens company’s business. The hand cream formula bought from Eastman was marketed originally as “Jergens Benzoin and Almond Lotion Compound,” and later simply as “Jergens Lotion.” It proved to be an instant success and rocketed Jergens to the top of the newly emerging field of skin care products. Expanding upon the model of the varied line of Woodbury soaps, by 1911, Jergens was marketing 82 brands of fragranced soaps, mostly under the Jergens name. But the Woodbury soaps were proving as troublesome as they were profitable. Around 1906, Dr. John Woodbury claimed that Jergens had breached the 1901 purchase agreement by not following the prescribed medicinal formula for his Woodbury soaps, marketing cheap tallow soap as “Woodbury Soap” instead. Woodbury marketed his original formula under his own name as a “Woodbury’s New Skin Soap.” Jergens was forced to sue Woodbury for an injunction to bar him from marketing soap under his own name, since Jergens owned the rights to the Woodbury name under the 1901 agreement. By then, Jergens had brought the J. Walter Thompson agency in to create a new advertising campaign to market the Woodbury soaps, leading ultimately to the wildly popular slogan “A Skin You Love To Touch” (modified in the 1920s to “The Skin You Love To Touch”). While it is difficult to measure why this campaign produced such an iconic slogan and remained effective as a branding tool for so long, some observers have suggested the slogan’s success was rooted in its being the first subtle injection of sex into advertising. After litigation in a variety of courts as intricate and protracted as Dickens’ Jarndyce v. Jarndyce, in 1921, Woodbury’s cousin, William, ultimately extricated, by means of a tiny sliver of trademark rights held back in the original 1901 contract of sale, the right to produce a line of products under his own name, but not John’s. Further litigation between the company and William Woodbury circumscribed even that right in 1927, and as late as 1938, the various Woodbury interests were still suing each other over who owned what residual rights to the Woodbury name under the 1901 contract.

Mr. & Mrs. Jergens

Andrew Jergens, always portrayed as hard working and frugal, remained at the head of his company until his death in January, 1929. His son Andrew N. Jr., born in 1881, succeeded him as president. Junior apparently was not terribly close to his driven father, but, nevertheless, as a dutiful son, started at the bottom of the company and worked his way up. When radio developed as an advertising medium in the 1920s, Senior endorsed the medium by diverting a portion of his advertising budget into radio advertising. Under Junior, the company sponsored Bing Crosby and Bob Hope in the 1930s, Walter Winchell, the most-listened-to and influential radio political columnist of his day, from 1932 to 1948, and Louella Parsons, his counterpart as a Hollywood gossip columnist between 1944 and 1954.

The company also innovated in the areas of using movie star endorsements and pioneered in marketing cosmetics in chain stores rather than beauty specialty shops. Along with strong advertising, the company produced new and more daring products, such as roll on deodorants and bubble bath, so that it was solid and established in the beauty care field when Junior died in 1967. American Brands, Inc. purchased the company in 1970, and a Japanese company, the Kao Corporation, purchased it from American Brands in 1988. As a wholly owned subsidiary of Kao, Andrew Jergens Company purchased the John Frieda Professional Hair Care Products business in 2002. While the company name was officially changed from Andrew Jergens to Kao Brands in 2004, the Andrew Jergens Company is still listed on the web as having a street address and telephone number in Cincinnati and new Jergens products are readily available on the web.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%5B1%5D.jpg)

%5B1%5D.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)