As explained in prior blogs, the tax on an initial sale of stock was .05/$100 in face value or fraction thereof; and the tax on a resale of stock was .02/$100 in face value or fraction thereof. If, however, an owner appointed a third party to sell the stock then an additional tax of 25-cents was due. The War Revenue Law levied a 25-cent tax on all power of attorney appointments that involved financial transactions.

Actually we've blogged previously about the power of attorney tax on a stock sale. Before becoming a regular guest on 1898revenues, I helped answer a reader's query about the tax on some

Mexican Telephone Company stocks.

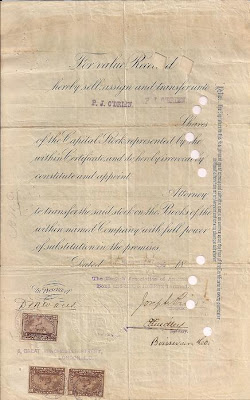

Now I'm the one needing help. The $1,000 stock certificate for the Kansas, Missouri, and Texas Railway Company (The Katy) shown below was initally issued October 31, 1890 well before the Spanish American War tax era. So its initial sale to the English Association of American Bond and Shareholders Ltd. (EAAB&S) wasn't taxed, but a resale was taxed in the US on January 12, 1901 and that resale included a power of attorney transaction. It's what transpired between those two events that's hazy.

$1,000 Stock Certificate Kansas, Missouri, and Texas Railway Company

Originally issued 31 October 1890

A single Great Britain Transfer Duty 2 shilling revenue stamp appears in the upper right corner. Presumably it paid the tax on the transfer of this stock to P. J. O'Brien on 17 November 1900, just 17 days after EAAB&S purchased it. I'm guessing P. J. O'Brien was an EAAB&S member who requested registration of this certificate in his personal name, an EAAB&S option as described in their advertisments appearing in

The Railway News and Joint-Stock Journal.

Great Britain Transfer Duty 2 Shilling Blue

An undated circular handstamp cancel depicting the heraldic lion and crown from The Netherlands coat of arms flanked on the left by the numerals "7,50" and on the right by the letters "Gl" with the letter "l" underlined also appears on the front of the certificate.

Can anyone identify and explain the exact significance of this handstamp?

It likely is related to Boissevain & Co. as described below.

UPDATE April 21: Mike Mahler advises the handstamp is from the Netherlands province of "Noord Holland", and that's the wording appearing at the top of the handstamp. He, too, believes it to document a tax payment there of 7.50 guilders. Amsterdam, home office of Boissevain & Co., is located in Noord (North) Holland.

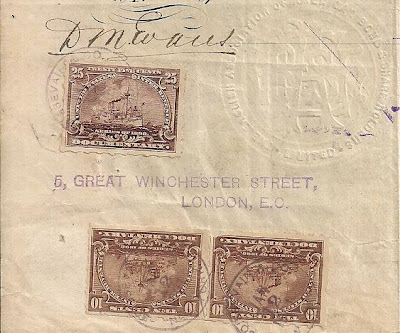

Completed transfer form on reverse side

As with this stock certificate, a preprinted transfer form often appears on the reverse side. EAAB&S used it to effect the aforementioned transfer to P. J. O'Brien on 17 November 1900. Deveremy Toler is faintly handstamped in the space provided for naming the transfer attorney. Both the Director and Secretary of the EAAB&S, along with one witness, signed the transfer authority. Those signatures are tied with a raised impression of the EAAB&S corporate seal. The address of the EAAB&S, 5, Great Winchester Street, London, E.C. is handstamped below the seal toward the left side.

So what's with the battleship revenues in the bottom left corner straddling the handstamped address of the EAAB&S? Well.....I'm not exactly certain, but obviously this certificate was returned and cancelled at some point as it was pasted back into the railroad's original stock stub book. When that occurred is unclear, but most likely on or around January 12, 1901, the date the battleship stamps were cancelled.

Cancellation Detail of Boissevain & Co.

Jan/12/1901

New York

and impression of the EAAB&S seal

Boissevain & Co., a Dutch firm with offices in Amsterdam, New York and London presumably was responsible for the curious 7,50 Gl handstamp on the front.

Further, as their New York CDS appears on the battleship stamps, they appear to have effected the return/repurchase/redemption/cancellation of this certificate by "The Katy", although the specific reason for its return is not identified.

Did Boissevain hold the certificate in trust for Mr. O'Brien on behalf of the EAAB&S ever since 1890? Or did Mr. O'Brien hold the certificate and simply use Boissevain to effect its eventual return/resale to The Katy?

Obviously, Boissevain felt obligated to pay both a resale tax of 20cents represented by the two 10-cent battleship stamps, as well as a power of attorney tax of 25 cents represented by the 25-cent battleship stamp. Numerous pinholes suggest additional instructions may have been attached at some point, but they are now lost to time.

My explanation, like the document itself, is a bit hazy, but it does illustrate payment of the resale and power of attorney tax during the Spanish American War Tax era.

This certificate demonstrates a multiply taxed doument by three national taxing authorities: Great Britain, The Netherlands province of Noord Holland, and the United States.

"The Katy" was first organized in 1865 and mostly provided passenger and freight service to Texas from the middle America market, eventually providing access to the Texas port of Galveston. Today it is part of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Can anyone identify and explain the exact significance of this handstamp?

Can anyone identify and explain the exact significance of this handstamp?