On Beyond Holcombe by Malcolm A. Goldstein appears on Sundays at 1898 Revenues.

Cresols are organic compounds characterized by a methyl

group (CH3) attached to a phenol molecule (a benzene ring with a

hydroxyl radical (OH) already bonded to it).

By definition, they occur in nature as components of pitch and bitumen,

and had been used without specific identification as parts of these

undifferentiated materials for medicinal purposes since antiquity. First

recognized as separate chemicals and refined in the 1830s, these compounds

themselves were, as will be discussed below in detail, produced by distilling

coal tar, itself originally regarded as a useless by-product of the reduction,

or controlled burning, of wood or coal.

The medicinal utility of cresols was debated throughout the 19th

Century. They were employed as

antiseptics and disinfectants, but as the concentration of the cresols

increased in a substance, the potential to burn also rose in direct proportion.

While a number of companies that cancelled battleship revenues built their

fortunes on clever uses of cresol compounds (and those companies will be

encompassed by this study), eventually, the compounds themselves were replaced

for most medical purposes by others that had the same beneficent power to

disinfect without the concomitant danger of injury.

The major figure that

emerges from the history of Vapo-Cresolene is George S Page, who really plays

only an indirect role in its story.

While today, to the extent he is remembered at all, he is known as a

sportsman, he was also a pioneering businessman, and deserves his place among

the industrial barons of the Nineteenth Century, with all of the both good and

bad connotation that title evokes. If Vapo-Cresolene was an afterthought or

off-shoot of a more important venture to him, it has endured to eclipse his

memory and lives on in our collective imagination, because of its still available advertisements and

vaporizers, and is stitched into our collective image of art nouveau.

According to Mustacich and Giacomelli, the Vapo-Cresolene

Company can be conclusively linked to only a single printed cancel appearing on

RB 28. Hardly worth a mention in

philatelic annals, right? Perhaps such

willful ignorance animates those battleship specialists whose principal joy is

discovering new intricacies in the line arrangement or millimeter spacings

among printed cancels. Since this study

focuses on the wider implications of patent medicine companies, the immense

volume of this company’s advertising in contemporary newspapers, magazines and

journals and the lingering existence of its iconic lamps (ever discovered in

dusty corners of flea markets, in antique stores and available on line), argue

for its enormous success both as a patent medicine industry competitor and as a

cultural force worth examining.

Even philatelically, there ought to be more to

Vapo-Cresolene’s story. The sheer

enormity of its presence in both the past and present markets seem to require a

larger philatelic footprint. Mustacich

and Giacomelli do identify one hand-stamped “V.-C.Co” cancel observed on an RB

28 that probably ought to be matched with this company. Other un-attributed “V. C. Co.” cancels

appear on values other than RB 28. These cancels may or may not coincide with

the Company’s product line, which did include both replacement parts and

replenishment bottles of the liquid used in its system. Two un-attributed hand-stamps (only one of

which appears on an RB 28) that otherwise might match - “T V C” and “T V &

Co” - just miss alignment with the company’s name, even though that name

sometimes appears in advertising as The Vapo-Cresolene Co. Maybe this article will persuade collectors

of all flavors - stamps, bottles, lamps, antiques - to take another look at

their boxes and revenue stamp pieces to see if they can find more cancelled

battleships that are definitively Vapo-Cresolene’s.

Vapo-Cresolene was popular.

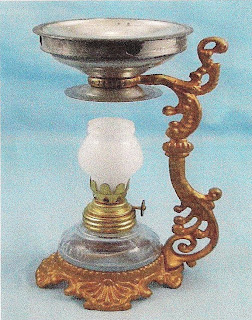

The Vapo-Cresolene box appeared large, yellow, and solid on the

druggist’s shelf. When opened, it contained

a small glass lamp, a sturdy, heavy, but gracefully molded, iron stand with an

opening at the bottom to hold the lamp and an arm at the top suspending a

vaporizer tray over the opening for the lamp, together with a bottle of

Cresolene, a spare lamp wick, and instructions.

The instructions told the user to fill the lamp with kerosene only -

alcohol would explode - and turn the flame up as high as manageable without

causing smoke for the first fifteen minutes.

Once the lamp was producing heat, it was placed in the stand under the

Vaporizer tray.

However distinctively idiomatic the lamp and stand were and

remain, it was the Cresolene, a sticky black liquid, that constituted the therapeutic core of the

device. The Cresolene was poured into

the tray and allowed to vaporize over the lamp flame in a ventilated room, and

was intended to disinfect the space into which it permeated. The company

advertised the Vapo-Cresolene system to be effective in treating respiratory

diseases such as croup, catarrh, diphtheria, whooping cough, scarlet fever and

asthma, by destroying the disease producing microbes in the patient’s system

when the vapor was inhaled. While

Cresolene was the company’s proprietary formulation, the American Medical

Association’s analysis in 1908 found it to be no more or less than garden

variety cresol as described in the United States Pharmacopoeia, the official

scientific compilation of medical compounds used in the United States. (Recall

that the eminent scientist, Dr. Lyon of Nelson, Baker & Co, served on the

1900 decennial revision committee for that document.)

As for the public’s use of the Vapo-Cresolene vaporizer

system, since the therapy was accepted as potentially medically useful,

although marginal at best since the inhalant had to be kept quite mild to avoid

being poisonous, all the AMA article could conclude - much in the same manner

as Consumer Reports does now for consumer goods - was that the Vapo-Cresolene

system was unnecessarily expensive without producing any greater beneficial

effect than any inexpensive generic equivalent cresol compound: “ This report

indicates that Vapo-Cresolene is a member of that class of proprietaries in

which an ordinary product is endowed, by the manufacturer, with extraordinary

virtues. The type is so common and has

been referred to so frequently that but for the dangers attendant on the

inhalation of any of the phenols, this particular product need not have been

mentioned.”

Vapo-Cresolene, as a patent medicine business, resulted from

the merging of the talents of one James Henry Valentine, the inventor of the

vaporizer system, and George Shepard Page.

Sadly, Valentine’s character and personality do not emerge clearly from

current records. In a history of

Chatham, NJ, he is portrayed as the man who singularly and successfully used a

“coal tar acid named Cresolene” as a vapor to relieve the discomfort of his

child suffering from whooping cough.

However, because he did not have sufficient money to follow through with

his idea, he soon turned the operation of the vaporizer business over to

Page. The government issued its first

patent for the vaporizing system in 1881 to one Elias H Carpenter. Carpenter immediately assigned the patent to

Valentine, who, in turn, assigned a one-half interest to George Page. Valentine owned parts of several patents

obtained from the 1880s to 1903, in connection with improvements made the lamp apparatus

as well as for the bottles used for Vapo-Cresolene, and, although he ought to

have drawn some monetary benefit for himself (as well as his sick daughter)

from these patents, he is remembered now only for his intuitive tinkering and

otherwise fades quickly from the history of the Vapo-Cresolene Company. A possible consequence of his exit is that a

James H Valentine is listed as a director of the Vaporia Medicine Co, which

filed in New Jersey for a corporate certificate in 1900, and in 1901 maintained

its own offices in New York City. This company, which, coincidently, also

marketed a coal tar derivative vaporizing system, became the Varoma Medicine Co

in 1902, and promptly appointed as its agent another battleship cancelling

company, wholesale druggist W H Schieffelin & Co (yet another story for

another day).

George S. Page

George S Page (1839-1892) was already rich when he first

encountered Valentine. Born in Redfield,

ME in 1839 and educated in Chelsea, MA, by 1879, Page had both control of the

essential ingredient, Cresolene, and the financial expertise and means to fully

develop Valentine’s vaporizer idea. Because of his own comfortable situation,

he was delighted to finance Valentine’s vaporizing venture as a side business

to his own. Because the Pages conducted

the Vapo-Cresolene business, had the wealth, and attracted its attendant

contemporary publicity, they have earned whatever kind of immortality articles

such as these produce.

Page’s career and fortune arose from the production of coal

gas and the discriminating refinement of coal tar. After briefly attempting to make his fortune

in the West as a young man, he returned to work with his father at Samuel Page

& Son of Boston, MA, a company which specialized in the distillation of

paraffin oils, wax and mineral oil then used as the purest and choicest of

illuminating materials, from the by-products of that reduction, of wood,

certain minerals or coal. By 1800,

scientists also had discovered the secret of extracting coal gas as another

by-product from the reduction of coal.

This process, in turn, became one of the growth industries of the first

half of the Nineteenth Century because coal gas was the first product that

could be both manufactured and distributed cheaply to illuminate the lamps of

cities at the dawn of the “gas light era.”

(Natural gas came decades later.)

Coal gas production became, in essence, the first indispensable

utility. Coal tar, itself a mixture of

some two hundred different substances, was also a by-product of the reduction

of coal. To virtually all of those who were busy cashing in on the coal gas

boom to illuminate cities, coal tar was an oily, thick, dirty substance often

considered worse than useless. Page not only applied the talents he had learned

working for his father to jump into the field of coal gas production, but he

also made the vital connection that coal tar itself could be further refined

into usable pitch, a material then most notably used as a water-sealant for

caulking ships, or in Page’s observation, as a paving material to lay a sidewalk.

Page himself often recounted the story of his life-altering

discovery. He noticed a group of workmen laying a pitch sidewalk during a visit

to Salem, MA, and took from them some of the pitch they were using. He then went to the local Salem gas works, where

he procured some coal tar. On the

following morning, he returned to the paving site and presented the foreman of

the job with the sample of pitch the foreman had given him together with a

sample of pitch he had produced from the coal tar by-product of the Salem gas

works. The foreman chose Page’s product

as superior, and a new paving material industry was born in that instant.

Necessity might also have driven Page’s brilliant insight because just at the

same moment he experienced his epiphany in Salem, commercial petroleum was

becoming available from Pennsylvania to supplant paraffin as the finest and

most brilliant illuminating material. Page was bright and quick enough to

observe that he had to expand his horizons beyond paraffin production.

By 1865, as well as his coal gas production interests, Page

was associated with the firm of Page, Kidder & Fletcher, which in 1872

morphed into a stock corporation, the New York Coal Tar Chemical Co, known for

producing roofing and water proofing material, as well as a range of

commercially useful chemicals, such as carbolic acid, naphtha, benzol, and

ammonia sulfate, all from coal tar.

Page’s fortune was created by his clever application of scientific advances

and redoubled by his shrewd investment in the capricious stock market of his

era, although his career in industry also continued from highlight to

highlight. He was responsible for

introducing to the United States several new generations of European technology

for improving the refinement of coal tar to produce purer and more precise

derivative compounds, each of which rewarded him with a fresh fortune. He also

played a significant role in the gas industry itself, negotiating at one point,

for example, among warring factions of gas producers in St. Louis to resolve

their differences and form an efficient (and probably monopolistic) combine.

Page played as hard as he worked. He was, as an obituary characterized him, “an

ardent sportsman, and his love for the rod, gun, dog and field was second only

to his fealty to the gas industry.” By 1888, he had created an estate of

several hundred acres called “Stanley” in honor of his mother’s maiden name, in

the Orange Hills near Chatham, in Morris County, NJ, had settled down to the

life of a country squire and had separated himself from the day to day

operations of his chemical company. He was a driving spirit behind the U.S.

Fish Commission, a government agency which was among the earliest to apply

scientific methodology to fish breeding, was the president of the Chatham, NJ

Fish and Game Protective Association, and vice-president of the American

Fish-Culturist Association. He was instrumental in the development of Rangeley,

ME as a fishing and hunting destination.

The breeding records of his kennels, also developed with his son Albion

as a commercial business and known as the Dunrobin Kennels, are enshrined in

the archives of the American Kennel Club.

After his father’s death, Albion carried on in his father’s footsteps as

a sportsman. In 1900, his racing horses,

which garnered second prize at the Morristown Field Club, in Morristown, NJ,

team trials, were two chestnut mares named Vapo and Cresolene.

George S Page was also a noted philanthropist in his time,

serving as the president of the Howard Mission and Home for Little Wanders

. He was an active member of his

Congregationalist Church, superintendent of its Sunday School, and a vocal

advocate and supporter of public education. He was also a founder of the New

Jersey Temperance Association and its president for several years. When he died, quite suddenly at age 52, his

funeral was held, as the same contemporary obituary noted, at his “manor house

... amid a throng that represented every phase of the life of the district for

miles around.” That obituary, published

in the American Gas Light Journal issue of April 4, 1892, noted that his death:

caused a shock to many of our readers;

for it is hard to realize that a splendid physical development nourished by

carefully trained habits of abstemiousness and by strict attention to the laws

of nature and culture could be so closely allied to the swiftest summons of

death. In the prime of a vigorous

manhood, Mr. Page passed away, almost without warning, on the morning of

Saturday, March 26th, and with this going out was terminated the life that

animated the body of an impulsive though consistent, of a just but generous, of

a decided but not bigoted man. In fact, to write of him as dead is somewhat

difficult now. The time that separates

him from us does not seem sufficient to reconcile us to the knowledge that his

marked personality is at an end.

Strangely enough, aside from his mention in connection with

its funding, George S Page’s name does not really ever appear again in the

Vapo-Cresolene Company’s records.

However, Page had four sons and a daughter and there can be no doubt

this business, among all of George’s various interests, was carried on as a

family affair. By the 1880s, George Page’s oldest son Albion Lambert Page, had

become the President of the Company. Forty years later, a listing of the

Vapo-Cresolene Company’s directors in 1919 shows that Albion was still

entrenched as President and Manager of the Company as well as a director. George’s second son Harry de Bacon Page, was

Vice-President, Treasurer and a director.

George’s third son Lawrence S Page was Secretary and a director of the

Company. The remaining directors were

Raymond F Page, George’s fourth son, and George’s only daughter, Florence P

Ensign. The Company had begun operation

in 1879, had offices in New York City at different addresses on Fulton, Wall

and Cortlandt streets, and located its manufacturing plant in Chatham, NJ,

undoubtedly where George S could keep an eye on it as long as he remained

alive. It soon had its own offices in

Montreal, Canada and Durban, South Africa.

Its London agent was Allen and Hanburys, Ltd, already profiled in this

column. In 1901, its capitalization was

$75,000; by 1919 capitalization had doubled to $150,000.

Vapo-Cresolene’s vaporizer system was, and continued to be,

advertised widely for approximately 80 years.

Of course, used improperly, Vapo-Cresolene units could, and did, cause

harm. There was always the danger of

fire posed by an open flame in any lamp, and upset Vapo-Cresolene lamps and

stands accounted for some number of fires.

There were periodic reports in medical journals of near poisonings

caused by using the Vapo-Cresolene lamp in an improperly ventilated room,

although Vapo-Cresolene’s advertising stressed that it was most efficaciously

used in a closed room. On a least one occasion, in 1912, an infant died from

drinking the contents of an unattended Cresolene bottle, which everyone

understood to be poisonous if ingested. By

the 1920s, the Company branched into producing tablets to broaden its product

offerings, and by the 1940s, the government forced the company to tone down its

promises of cures for respiratory illnesses. Yet with all these drawbacks,

Vapo-Cresolene vaporizer units, eventually with electric heating elements

supplanting the kerosene lamps, continued to be produced until the 1950s. Why did the public embrace such an

inefficient and potentially dangerous system for so long? That question probably cannot be answered

precisely, but it can equally asserted that nothing has really changed. Medicine is often predicated on refining

poison. After all, Botox, the miracle

anti-aging drug of our times, is merely diluted botulism toxin, among the most

fatal and deadly substances known to man.

Vapo-Cresolene cancels from the collection of Henry Tolman

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment