On Beyonde Holcombe, by Malcolm A. Goldstein, appears on Sundays at 1898 Revenues.

William Radam, one of James Harvey Young’s celebrated “Toadstool Millionaires,” is a character whom everyone writing about patent medicines loves to hate, and finds easy to belittle and deprecate. The salient facts are simple. Radam manufactured one product, his Microbe Killer, which he patented in 1886 and marketed in vessels, often one gallon jugs, but later in smaller less expensive bottles as well, all decorated with an extremely eye-catching and flashy trademark. He claimed that microbes lay at the root of all disease, and that his Microbe Killer exterminated them all, and thus could defeat any and all disease. Its immediate, remarkable popularity propelled Radam from his nursery in Austin, TX to a mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York City in about two years’ time. His intellectual undoing was as just as quick and spectacular. Analytic chemistry, then in its infancy, was almost immediately interposed against Radam’s theory and his claims. Repeated chemical analyses easily demonstrated that his miracle elixir was virtually 99% water garnished with traces of potentially poisonous acids and flavored with a touch of wine! How, we now wonder, could anyone have acclaimed the Microbe Killer’s wondrous curative power even for a second?

Born in Prussia in 1844 and a veteran of its army, Radam emigrated to America in 1871. In 1890, wishing to explain and build upon his sudden fortune and prominence, Radam self-published a book in which he recounted his history and the manner in which he had come to develop his singular theory about disease and its cure. The tale ran thus: by 1884, he had become a gardener who owned small nurseries in and around Austin, TX. He had lost his two children to childhood illness and was himself a long term sufferer of intermittent malarial fever complicated by rheumatism and sciatica. He had tried every cure known to medicine, every patent medicine and folk remedy and had found no relief. His doctors told him his condition was irreversible, incurable and would shortly resolve itself into deadly consumption.

The news of his imminent death impelled Radam immediately to begin to research the causes of disease, and of consumption in particular. His study led him to review the theory of evolution, recently proposed by Charles Darwin, and the most recent kind of classification of plants and animals by common ancestor-developmental relationships which it had engendered, all of which he accepted as true. He further learned that the latest discoveries by the distinguished French scientist Louis Pasteur and the eminent German scientist Robert Koch had identified microscopic germs, recently denominated “microbes,” as the culprits causing disease. From his close perusal of the most recent publications, he ascertained that while science could accurately describe and classify these microbes, neither the scientists nor the doctors could proffer a satisfactory method for destroying them. In a wondrous leap of illogic, he then concluded that since microbes were the source of disease, the compound that would kill them would conquer disease.

Pondering these scientific insights together with his dismal fate, Radam turned to the plants for which he, as a gardener, cared, wondering if they possessed weapons to ward off the deadly onslaught of microbes about to overtake him. He theorized if he could discover the secret the plants used to protect themselves from microbes while themselves remaining viable, that substance might sustain him. After much laborious experimentation, sketched only in the most abstract detail, he found the right substance to expunge microbes, tried it upon himself and found himself growing stronger. He kept dosing himself with his own medicine and within a year he felt himself completely cured. Describing himself as a “cautious and prudent” man, he then determined to see whether his substance would have the same effect on others, and began to seek out around him other chronically ill people whose cases lay beyond the help of established medicine. He provided his treatment free, collecting only testimonials in return, and finally became so involved in producing his Microbe Killer that he neglected his nursery, had to leave his cherished livelihood, and trust his own financial well-being, as well as his health, entirely to his formula.

By 1886, he had patented his compound, and by the end of 1887 had registered with the government his vivid, compelling trademark image: a vigorous, healthy young man dressed in a suit about to club a skeleton representing death, whose scythe has already been dashed from his bony hands and lies broken at his bony feet. He began advertising his Microbe Killer for sale by making a public declaration of his cure in the Austin Statesman newspaper issue of August 30, 1887.

Radam’s ad struck a nerve and galvanized the public. The Microbe Killer was an immediate hit. Within a year he built his first factory, which is today the Koppel Building in Austin, TX, and not long thereafter, he needed seventeen factories just within the United States to supply the demand. That hunger for Radam’s Microbe Killer extended beyond the shores of the United States. Soon Radam had sales agencies and factories stretching from London to Melbourne, Australia. The 1890 book laid bare in complex detail the reasoning underlying his microbe theory of disease, and was laced with plenty of the latest microscopic pictures of disease causing microbes. It was augmented by the story of his own personal struggles and further enriched with photos of the very plush surroundings he now occupied. The mansion formerly had been owned by J. C. Fisher, founder of the Fisher Piano Company. As a publicist for his product, Radam was no fool. He put forward his thesis, proclaimed that he would be excoriated by the established medical community, and, reckoning that a large segment of the public distrusted doctors, challenged that community to disprove his reasoning.

Almost instantaneously, Dr. R G Eccles, a pharmacist and doctor at Long Island College Hospital entered the lists as a challenger to Radam. He stated that his own private chemical analysis (the first of many similar ones done by various professional and scientific groups) showed that Radam’s compound was water, mixed with the slightest trace of highly corrosive acids and wine. Eccles claimed that Radam was a “misguided crank” who was “out quacking the worst quacks of this or any other age” as well as realizing a 6000% profit on every jug he sold of his worthless concoction. Radam sued for libel on the grounds that there were no acids in his mixture and Eccles countersued in the amount of $20,000, also for libel, because Radam denounced him as a charlatan. Although defended by one of the great iconoclastic thinkers of the time, the agnostic Robert Ingersoll, Radam lost the first round to Eccles, whose libel action against him filed in Brooklyn came to trial first. Radam made a poor witness on his own behalf, being unable to make elementary plant classifications when challenged as a gardener, and his own expert witness admitted that there were, in fact, acids in the Microbe Killer. The jury awarded Eccles $6000 against Radam, who promptly fired Ingersoll, and later managed to have the verdict overturned on appeal. Meanwhile, Radam, who did not testify again, obtained a favorable ruling on his lawsuit against Eccles filed in Manhattan, when the judge directed that the jury enter a verdict in favor of Radam on the technical grounds that the legal defense presented by Eccles was too general and not specific enough to answer Radam’s charges. So instructed, the jury brought back an award for Radam in the amount of $500.

Having won a small verdict on a technicality, Radam declared himself entirely vindicated, and redoubled his advertising, emphasizing the favorable ruling. While Eccles and Radam continued to spar and berate each other, and other professional organizations quickly joined Eccles in inveighing against him, Radam’s legal “victory” pointed the way toward his future strategy for dealing with scientific carping at his reasoning and methodology; he simply ignored it, figuring that the people to whom his “medicine” appealed thought as little of doctors as he did. Sales did not flag and Radam’s shrewd calculation was sustained. While the trade journals and professional magazines continued to flail away at Radam, the exorbitant profits rolled in for the rest of his life, which ended in 1902, perhaps too soon and too abruptly for one as fortified against disease as Radam. He was buried in his beloved Austin, TX.

The Microbe Killer remained on sale, even if advertised a little less conspicuously and flamboyantly after Radam’s death. Ownership of the business and trademarks passed to Ida Haenel Radam, his widow and beneficiary, whose name appears on the trademark applications after 1902. She seems to have retreated to Austin and left the management of the company to others. A 1904 trade publication advertisement noted that the Microbe Killer was now being made available through all jobbers instead of through Radam’s own restrictive and exclusive prior marketing arrangements. In 1905, one Walter W Bostwick (a sometime inventor who in 1897 was involved in an attempt to form a nationwide trust to control the patent leather industry) sued in the courts of New York for foreclosure against the company over the objection of the board of directors. Bostwick alleged he owned all of the bonds of the company; the directors claimed that the mortgage backed by the bonds had been rescinded. The court merely appointed a neutral trustee of the mortgage and left the parties to sort out the dispute. A 1912 New York Times article, reporting on the suicide of real estate broker Arthur S Levy, who, apparently despondent over ill health at age 58, administered one shot to himself from an “eight shot British bulldog revolver” in his Broadway brokerage office, identified Levy as the “President, Treasurer and Director of the William Radam Microbe Killer Co.” In 1915, Gordon S. P. Kleeberg of the New York City law firm of Myers & Goldsmith is listed as the President and Director of the company. Kleeberg (1883-1946) wrote a history of the Republican Party in 1911 and argued some significant tax cases before the Supreme Court, but seems to have had little direct connection to the patent medicine business beyond holding the company titles.

The change in the public’s attitude toward the Microbe Killer came quite slowly. On November 28, 1905, Radam’s Microbe Killer was denounced as a completely fraudulent “medicine” in the lead paragraph of the third in the series of articles entitled “The Great American Fraud” written by a muckraking reporter named Samuel Hopkins Adams for the weekly general circulation publication, Collier’s Weekly Magazine. Because Radam was already dead, even Adams treated the revelation of the fraud underlying Radam’s Microbe Killer as old news, and devoted the bulk of his article to denouncing another very similar “medicine” which was then stealing some of the Microbe Killer’s thunder as the latest miracle cure. However, the hoopla created by the “Great American Fraud” finally raised public awareness high enough for people to demand protection against outright fraud.

The result was the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the first attempt to regulate the pharmaceutical and drug industry, which concentrated on removing adulterated and misbranded food and medicine from interstate commerce, and created the federal Food and Drug Administration. It was a first baby step, for the Act, as originally passed, required essentially only that the substance of the “medicine” match the substance identified on the label. However, only the most dangerous or poisonous substances, like alcohol or cocaine, actually had to be listed on the label. Since the Microbe Killer genuinely contained neither alcohol nor drugs, it easily slid past the narrowly defined constraints of the original Act, and proudly bore on its post-Act label, as did so many other equally implausible concoctions that remained on the market, “Guaranteed By The Wm Radam Microbe Killer Co under the Food And Drug Act of June 30, 1906." The medical and scientific communities were doubly outraged not only that the Act did nothing to remove the Microbe Killer from the marketplace, but also that the company and others could imply the government’s endorsement by stating that the Microbe Killer was “guaranteed” to be in compliance with the Act. The American Medical Association denounced the Microbe Killer in 1910.

The obvious solution was for the newly authorized Food and Drug Administration to take some further regulatory action, and so it did.. In 1912, the government persuaded Congressman Swagar Sherley of Kentucky to sponsor an amendment to the 1906 act that broadened the definition of a misbranded, and therefore illegal, substance, to include one where the label made claims concerning the “curative or therapeutic effect” of the medicine that were false or fraudulent. Congress passed the Sherley Amendment with much less fuss than the controversy that had surrounded the original Act, and William Howard Taft, now the president, signed it into law. With its power to regulate re-defined to include not just false claims about the ingredients of the medicine, but its efficacy as well, the FDA made the attack on the Microbe Killer one of its top priorities. A shipment of 539 boxes of bottles and 322 cartons of jugs was seized in transit between New York and Minneapolis, and the FDA brought its case against the Microbe Killer to Minneapolis in 1913. The FDA’s Chief Chemist himself testified that the Microbe Killer was actually 99.381% water and the only physiological effect of the trace of sulfuric acid contained in the balance would be to irritate the stomach lining. The Chief Chemist further opined that the contents of the shipment cost $25.82 to manufacture as against a retail value of $5,166. With Radam long dead, the Microbe Killer Co. lacked an effective spokesman to attest to the credulity of the many testimonials, stockpiled since Radam began collecting them in 1886, it introduced to offset the FDA’s Chief Chemist. The jury in Minnesota accepted the FDA’s testimony, and the entire shipment of Microbe Killer was condemned as illegally misbranded and destroyed in a public display of breaking and burning.

While the destruction of that shipment of Microbe Killer in 1913 ought to have spelled the immediate end of the company, amazingly, it was still clinging to life as a business in 1922, when a New York Times article noted that its capital was being reduced from $260,000 to $25,000, a sure sign of corporate anemia. While the company disappears from the public records after that time, Ida Radam herself made one last brief news splash in 1929. At age 77, she journeyed from her home in Austin, TX back to New York City to re-arrange her investments. Ignoring the advice of her bankers, who said they would make the transfer from New York to Austin on her behalf, she insisted on personally carrying $63,000 worth of New York City bonds with her out of the bank. She then left them in a package on the back seat of the taxicab she took from the bank to Penn Station to return to Austin. The story does have a happy ending. The bonds were non-negotiable, and were returned to her again some eight months later, when an unidentified man turned the package in at Penn Station. Since the Crash of 1929 had occurred between these two events, it is difficult to calculate just how much relief Ida must have felt upon their return.

Between 1887 and 1902, William Radam bucked scientific and medical opinion, as well as defying common sense, by invoking modern science with the true fervor of a zealot. Manipulating from a base of solid scientific research established by men such as Pasteur and Koch, he drew only the conclusions he desired, and let the earnestness of the pseudo-science he embroidered on top of the genuine knowledge answer his detractors. In an age of mistrust about matters both medicinal and scientific, his passion sustained the profitability of his Microbe Killer for not less than 30 years, as well as bestowing upon us that lingering and unforgettable trademark image of a healthy, well dressed young man clubbing the skeleton of death.

William Radam

William Radam, one of James Harvey Young’s celebrated “Toadstool Millionaires,” is a character whom everyone writing about patent medicines loves to hate, and finds easy to belittle and deprecate. The salient facts are simple. Radam manufactured one product, his Microbe Killer, which he patented in 1886 and marketed in vessels, often one gallon jugs, but later in smaller less expensive bottles as well, all decorated with an extremely eye-catching and flashy trademark. He claimed that microbes lay at the root of all disease, and that his Microbe Killer exterminated them all, and thus could defeat any and all disease. Its immediate, remarkable popularity propelled Radam from his nursery in Austin, TX to a mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York City in about two years’ time. His intellectual undoing was as just as quick and spectacular. Analytic chemistry, then in its infancy, was almost immediately interposed against Radam’s theory and his claims. Repeated chemical analyses easily demonstrated that his miracle elixir was virtually 99% water garnished with traces of potentially poisonous acids and flavored with a touch of wine! How, we now wonder, could anyone have acclaimed the Microbe Killer’s wondrous curative power even for a second?

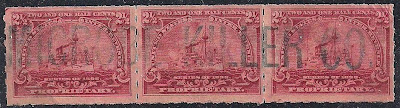

MICROBE KILLER CO.

handstamp running across three stamps

Born in Prussia in 1844 and a veteran of its army, Radam emigrated to America in 1871. In 1890, wishing to explain and build upon his sudden fortune and prominence, Radam self-published a book in which he recounted his history and the manner in which he had come to develop his singular theory about disease and its cure. The tale ran thus: by 1884, he had become a gardener who owned small nurseries in and around Austin, TX. He had lost his two children to childhood illness and was himself a long term sufferer of intermittent malarial fever complicated by rheumatism and sciatica. He had tried every cure known to medicine, every patent medicine and folk remedy and had found no relief. His doctors told him his condition was irreversible, incurable and would shortly resolve itself into deadly consumption.

The news of his imminent death impelled Radam immediately to begin to research the causes of disease, and of consumption in particular. His study led him to review the theory of evolution, recently proposed by Charles Darwin, and the most recent kind of classification of plants and animals by common ancestor-developmental relationships which it had engendered, all of which he accepted as true. He further learned that the latest discoveries by the distinguished French scientist Louis Pasteur and the eminent German scientist Robert Koch had identified microscopic germs, recently denominated “microbes,” as the culprits causing disease. From his close perusal of the most recent publications, he ascertained that while science could accurately describe and classify these microbes, neither the scientists nor the doctors could proffer a satisfactory method for destroying them. In a wondrous leap of illogic, he then concluded that since microbes were the source of disease, the compound that would kill them would conquer disease.

Pondering these scientific insights together with his dismal fate, Radam turned to the plants for which he, as a gardener, cared, wondering if they possessed weapons to ward off the deadly onslaught of microbes about to overtake him. He theorized if he could discover the secret the plants used to protect themselves from microbes while themselves remaining viable, that substance might sustain him. After much laborious experimentation, sketched only in the most abstract detail, he found the right substance to expunge microbes, tried it upon himself and found himself growing stronger. He kept dosing himself with his own medicine and within a year he felt himself completely cured. Describing himself as a “cautious and prudent” man, he then determined to see whether his substance would have the same effect on others, and began to seek out around him other chronically ill people whose cases lay beyond the help of established medicine. He provided his treatment free, collecting only testimonials in return, and finally became so involved in producing his Microbe Killer that he neglected his nursery, had to leave his cherished livelihood, and trust his own financial well-being, as well as his health, entirely to his formula.

By 1886, he had patented his compound, and by the end of 1887 had registered with the government his vivid, compelling trademark image: a vigorous, healthy young man dressed in a suit about to club a skeleton representing death, whose scythe has already been dashed from his bony hands and lies broken at his bony feet. He began advertising his Microbe Killer for sale by making a public declaration of his cure in the Austin Statesman newspaper issue of August 30, 1887.

Radam’s ad struck a nerve and galvanized the public. The Microbe Killer was an immediate hit. Within a year he built his first factory, which is today the Koppel Building in Austin, TX, and not long thereafter, he needed seventeen factories just within the United States to supply the demand. That hunger for Radam’s Microbe Killer extended beyond the shores of the United States. Soon Radam had sales agencies and factories stretching from London to Melbourne, Australia. The 1890 book laid bare in complex detail the reasoning underlying his microbe theory of disease, and was laced with plenty of the latest microscopic pictures of disease causing microbes. It was augmented by the story of his own personal struggles and further enriched with photos of the very plush surroundings he now occupied. The mansion formerly had been owned by J. C. Fisher, founder of the Fisher Piano Company. As a publicist for his product, Radam was no fool. He put forward his thesis, proclaimed that he would be excoriated by the established medical community, and, reckoning that a large segment of the public distrusted doctors, challenged that community to disprove his reasoning.

Almost instantaneously, Dr. R G Eccles, a pharmacist and doctor at Long Island College Hospital entered the lists as a challenger to Radam. He stated that his own private chemical analysis (the first of many similar ones done by various professional and scientific groups) showed that Radam’s compound was water, mixed with the slightest trace of highly corrosive acids and wine. Eccles claimed that Radam was a “misguided crank” who was “out quacking the worst quacks of this or any other age” as well as realizing a 6000% profit on every jug he sold of his worthless concoction. Radam sued for libel on the grounds that there were no acids in his mixture and Eccles countersued in the amount of $20,000, also for libel, because Radam denounced him as a charlatan. Although defended by one of the great iconoclastic thinkers of the time, the agnostic Robert Ingersoll, Radam lost the first round to Eccles, whose libel action against him filed in Brooklyn came to trial first. Radam made a poor witness on his own behalf, being unable to make elementary plant classifications when challenged as a gardener, and his own expert witness admitted that there were, in fact, acids in the Microbe Killer. The jury awarded Eccles $6000 against Radam, who promptly fired Ingersoll, and later managed to have the verdict overturned on appeal. Meanwhile, Radam, who did not testify again, obtained a favorable ruling on his lawsuit against Eccles filed in Manhattan, when the judge directed that the jury enter a verdict in favor of Radam on the technical grounds that the legal defense presented by Eccles was too general and not specific enough to answer Radam’s charges. So instructed, the jury brought back an award for Radam in the amount of $500.

Having won a small verdict on a technicality, Radam declared himself entirely vindicated, and redoubled his advertising, emphasizing the favorable ruling. While Eccles and Radam continued to spar and berate each other, and other professional organizations quickly joined Eccles in inveighing against him, Radam’s legal “victory” pointed the way toward his future strategy for dealing with scientific carping at his reasoning and methodology; he simply ignored it, figuring that the people to whom his “medicine” appealed thought as little of doctors as he did. Sales did not flag and Radam’s shrewd calculation was sustained. While the trade journals and professional magazines continued to flail away at Radam, the exorbitant profits rolled in for the rest of his life, which ended in 1902, perhaps too soon and too abruptly for one as fortified against disease as Radam. He was buried in his beloved Austin, TX.

The Microbe Killer remained on sale, even if advertised a little less conspicuously and flamboyantly after Radam’s death. Ownership of the business and trademarks passed to Ida Haenel Radam, his widow and beneficiary, whose name appears on the trademark applications after 1902. She seems to have retreated to Austin and left the management of the company to others. A 1904 trade publication advertisement noted that the Microbe Killer was now being made available through all jobbers instead of through Radam’s own restrictive and exclusive prior marketing arrangements. In 1905, one Walter W Bostwick (a sometime inventor who in 1897 was involved in an attempt to form a nationwide trust to control the patent leather industry) sued in the courts of New York for foreclosure against the company over the objection of the board of directors. Bostwick alleged he owned all of the bonds of the company; the directors claimed that the mortgage backed by the bonds had been rescinded. The court merely appointed a neutral trustee of the mortgage and left the parties to sort out the dispute. A 1912 New York Times article, reporting on the suicide of real estate broker Arthur S Levy, who, apparently despondent over ill health at age 58, administered one shot to himself from an “eight shot British bulldog revolver” in his Broadway brokerage office, identified Levy as the “President, Treasurer and Director of the William Radam Microbe Killer Co.” In 1915, Gordon S. P. Kleeberg of the New York City law firm of Myers & Goldsmith is listed as the President and Director of the company. Kleeberg (1883-1946) wrote a history of the Republican Party in 1911 and argued some significant tax cases before the Supreme Court, but seems to have had little direct connection to the patent medicine business beyond holding the company titles.

The change in the public’s attitude toward the Microbe Killer came quite slowly. On November 28, 1905, Radam’s Microbe Killer was denounced as a completely fraudulent “medicine” in the lead paragraph of the third in the series of articles entitled “The Great American Fraud” written by a muckraking reporter named Samuel Hopkins Adams for the weekly general circulation publication, Collier’s Weekly Magazine. Because Radam was already dead, even Adams treated the revelation of the fraud underlying Radam’s Microbe Killer as old news, and devoted the bulk of his article to denouncing another very similar “medicine” which was then stealing some of the Microbe Killer’s thunder as the latest miracle cure. However, the hoopla created by the “Great American Fraud” finally raised public awareness high enough for people to demand protection against outright fraud.

The result was the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the first attempt to regulate the pharmaceutical and drug industry, which concentrated on removing adulterated and misbranded food and medicine from interstate commerce, and created the federal Food and Drug Administration. It was a first baby step, for the Act, as originally passed, required essentially only that the substance of the “medicine” match the substance identified on the label. However, only the most dangerous or poisonous substances, like alcohol or cocaine, actually had to be listed on the label. Since the Microbe Killer genuinely contained neither alcohol nor drugs, it easily slid past the narrowly defined constraints of the original Act, and proudly bore on its post-Act label, as did so many other equally implausible concoctions that remained on the market, “Guaranteed By The Wm Radam Microbe Killer Co under the Food And Drug Act of June 30, 1906." The medical and scientific communities were doubly outraged not only that the Act did nothing to remove the Microbe Killer from the marketplace, but also that the company and others could imply the government’s endorsement by stating that the Microbe Killer was “guaranteed” to be in compliance with the Act. The American Medical Association denounced the Microbe Killer in 1910.

The obvious solution was for the newly authorized Food and Drug Administration to take some further regulatory action, and so it did.. In 1912, the government persuaded Congressman Swagar Sherley of Kentucky to sponsor an amendment to the 1906 act that broadened the definition of a misbranded, and therefore illegal, substance, to include one where the label made claims concerning the “curative or therapeutic effect” of the medicine that were false or fraudulent. Congress passed the Sherley Amendment with much less fuss than the controversy that had surrounded the original Act, and William Howard Taft, now the president, signed it into law. With its power to regulate re-defined to include not just false claims about the ingredients of the medicine, but its efficacy as well, the FDA made the attack on the Microbe Killer one of its top priorities. A shipment of 539 boxes of bottles and 322 cartons of jugs was seized in transit between New York and Minneapolis, and the FDA brought its case against the Microbe Killer to Minneapolis in 1913. The FDA’s Chief Chemist himself testified that the Microbe Killer was actually 99.381% water and the only physiological effect of the trace of sulfuric acid contained in the balance would be to irritate the stomach lining. The Chief Chemist further opined that the contents of the shipment cost $25.82 to manufacture as against a retail value of $5,166. With Radam long dead, the Microbe Killer Co. lacked an effective spokesman to attest to the credulity of the many testimonials, stockpiled since Radam began collecting them in 1886, it introduced to offset the FDA’s Chief Chemist. The jury in Minnesota accepted the FDA’s testimony, and the entire shipment of Microbe Killer was condemned as illegally misbranded and destroyed in a public display of breaking and burning.

While the destruction of that shipment of Microbe Killer in 1913 ought to have spelled the immediate end of the company, amazingly, it was still clinging to life as a business in 1922, when a New York Times article noted that its capital was being reduced from $260,000 to $25,000, a sure sign of corporate anemia. While the company disappears from the public records after that time, Ida Radam herself made one last brief news splash in 1929. At age 77, she journeyed from her home in Austin, TX back to New York City to re-arrange her investments. Ignoring the advice of her bankers, who said they would make the transfer from New York to Austin on her behalf, she insisted on personally carrying $63,000 worth of New York City bonds with her out of the bank. She then left them in a package on the back seat of the taxicab she took from the bank to Penn Station to return to Austin. The story does have a happy ending. The bonds were non-negotiable, and were returned to her again some eight months later, when an unidentified man turned the package in at Penn Station. Since the Crash of 1929 had occurred between these two events, it is difficult to calculate just how much relief Ida must have felt upon their return.

Between 1887 and 1902, William Radam bucked scientific and medical opinion, as well as defying common sense, by invoking modern science with the true fervor of a zealot. Manipulating from a base of solid scientific research established by men such as Pasteur and Koch, he drew only the conclusions he desired, and let the earnestness of the pseudo-science he embroidered on top of the genuine knowledge answer his detractors. In an age of mistrust about matters both medicinal and scientific, his passion sustained the profitability of his Microbe Killer for not less than 30 years, as well as bestowing upon us that lingering and unforgettable trademark image of a healthy, well dressed young man clubbing the skeleton of death.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment